Saturday, February 6, 6 – 8 p.m.

All events are free and open to the public

This exhibition highlights works from the St. Catherine University Fine Art Collection done by student artists at Immaculate Heart College in Pasadena, CA in the 1950s under the tutelage of famed print artist Sister Corita Kent, better known just as Corita, and Sister Magdalen Mary Martin, known as Maggie. Themes of Social Justice, Art Activism, and Catholic Identity resonate with St. Kate’s vision and mission.

This exhibition is co-sponsored by the Myser Initiative on Catholic Identity, The Friends of the Gallery, and the Art and Art History Department

Curators Comments

Most of the works in this exhibition were created by students to be sold at low prices to the public in order to help fund the Immaculate Heart College (IHC) Art Department and its mission. This effort can be tied to changes being brought about in the American Liturgical Movement, which stressed the idea of intelligent participation in the liturgy through encouraging the faithful to create objects that had religious significance/value. This exhibition also serves as a vibrant illustration of the union of physical work and spirituality, a concept long embraced at St. Catherine’s, and it highlights the effect of a talented, visionary set of teachers on the work that their students were able to achieve.

These works were produced during a period on the brink of tremendous change—the 1950s. The decade was in many ways a positive one, with many Americans still riding the wave of victory after the end of World War II, feeling the benefits of the housing boom and other economic expansion, and espousing a sunny outlook toward the future. On the flip side, the 1950s can also be categorized as strident, normative, and not inclusive of many people in the United States, including people of color, women, and the poor. The 1950s also can be said to anticipate the turbulent movements of the 1960s, a decade marked by changing social norms, the rise of feminism, troubled race relations, and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

The economic reality for many Americans became progressively worse by the 1960s. Poverty affected areas of the country, from the Deep South to inner city inhabitants to suburbanites. In 1962 the federal food stamp program, which had not been active since the Great Depression, was revived. The Pilot Food Stamp Program ran from 1961-64, with further iterations of the law to follow.

Religion, too, found itself in trying times, regardless of denomination. Church attendance continued to fall in the face of changing culture and the busyness of people’s lives. The older, traditional ways of the church were becoming outmoded and needed to be refreshed and reconfigured to be able to connect with modern life.

All of these changes—political, economic, social, and spiritual—meant that the table was set, midcentury, for new messages and new art forms which felt contemporary and could speak to the issues quite large and present in people’s everyday lives.

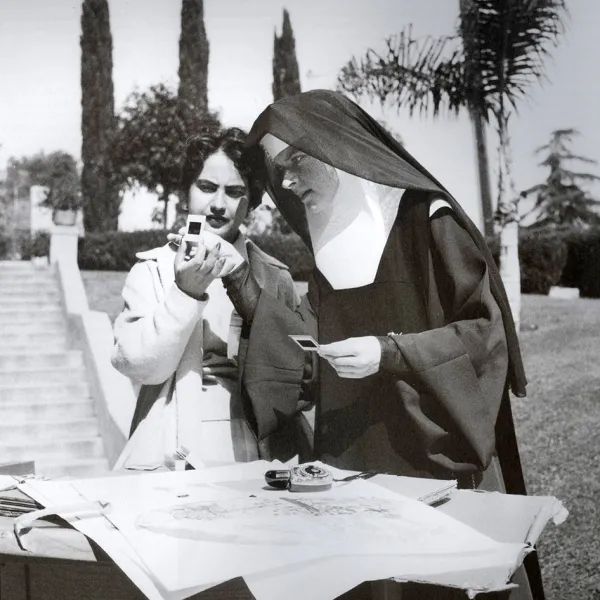

Teaching Art at IHC

Corita joined IHC in 1936 and became a protege and eventually a colleague of Sister Maggie, who chaired the art department there from 1936-1964. Maggie’s “energy, enthusiasm, and unconventional teaching methods set the standard for Corita,” who took over as chair in 1964. (Ian Berry & Michael Duncan, eds., Someday is Now, (Munich: Prestel, 2013), 12) The two worked closely together in teaching classes, supporting the department, and touring the country in order to show and sell artwork generated within IHC classes and by Corita herself. Corita and Maggie became an “indefatigable team dedicated to nurturing students and promoting the art department as a potent off-campus art-world force. Student projects became the showcase for their radical pedagogy.” (Berry, Someday is Now, 12)

Classes taught at IHC included drawing, painting, and printmaking, but also folk art techniques such as collage, mosaics, and sand casting. By the mid 1960s, Corita was enjoying a lot of fame, and many of the students studying art at IHC did so to be able to work with her. The college itself was said by many to have “reinvented Catholic cool, attracting poets, inventors, designers, filmmakers, and cultural luminaries to campus.” (Corita Kent and Jan Stewart, Learning by Heart (New York: Bantam, 1992), foreword.) Despite their working relationship, Maggie and Corita were never close, and by 1964, they effectively ended their collaboration. In 1968 Corita left the sisterhood and IHC, and in 1980 the school closed.

The style and approach of both Corita and Maggie in teaching art is notable. Maggie espoused the idea that students and teachers alike be deeply immersed in the art-making process and in comprehension of the world around them. She did not see herself as an artist, and even “frowned on the use of the term “art” in relation to her students’ work, believing that it impeded the experimentation and training of the eye that “play” fostered.” (Berry, Someday is Now, 11) Lucia Capacchione, one of artists in this exhibition and a student at IHC, states that Maggie “didn’t want people to think we were doing this whole precious art thing.” (Berry, Someday is Now, 37) Technical proficiency was OK, Capacchione notes, but “if Maggie and Corita felt one’s work was lacking in terms of the heart and soul beneath, “they’d call it right away. They’d[...]see it and they’d say ‘No, no, dead.’ ” (Berry, Someday is Now, 37)

Another IHC student, Janet Weber, recalls that the classes taught by Maggie were not quite as ‘soft’ as that of Corita, though the latter was also a demanding and precise presence. Weber recounts, “We had silkscreening with Magdalen Mary[...]she’d sit there and we’d pull a print and she’d criticize it. “Oh, soften that color, change that.” So she was like the master of the classroom and you followed her directions.” (Berry, Someday is Now, 38)

To aid student creativity and inspiration, Corita would encourage her students to pull from all sorts of sources to create their art, including that of billboards and newspaper print. There was also a spiritual aspect to this, because Corita thought deeper meaning could also be gleaned from such things. As she would later write, just as “when we learn (or teach) how to take fairy stories and myths and parables we must also learn (or teach) how to take billboards and magazine ads and TV commercials.[...]Thank God for city-scapes—they have signs. Thank God for magazines—they have ads.” (Sister Mary Corita Kent, Harvey Cox and Samuel A. Eisenstein, Sister Corita (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press), 11-12)

The Artists and the Messages

Many of the artists in this show are not well known, and indeed, for some of these works, we do not even know the artist’s name. However, some of these student artists did go on to successful careers as artists or other professionals. Barbara Pfeifer was a St. Catherine studio art major whose work was highlighted in the college’s student newspaper, The Wheel. We also know that she traveled to IHC in 1956 to take a summer session art class there. Lucia Capacchione is a well known and active art therapist.

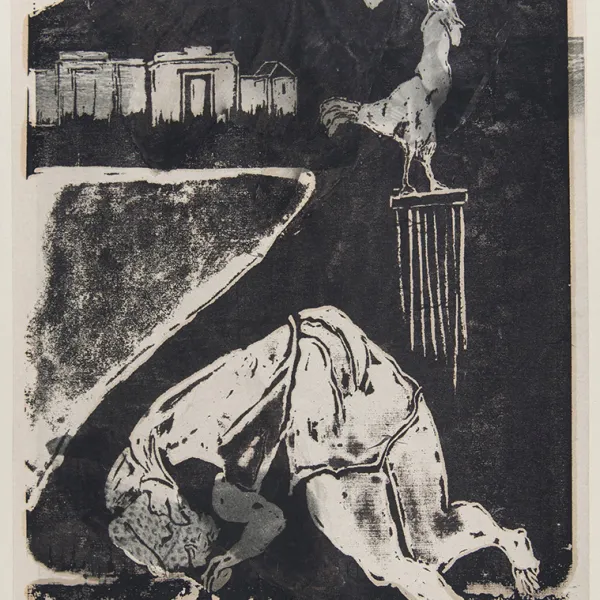

While it is impossible to completely categorize the works in this exhibition, certain rough themes arise upon their perusal. Many contain religious content, while others seem to explore the concepts, respectively, of labor and leisure. Furthermore, we see certain works which seem to be less political and more about creating lively and colorful artistic expression, using more established artists as a jumping off point.

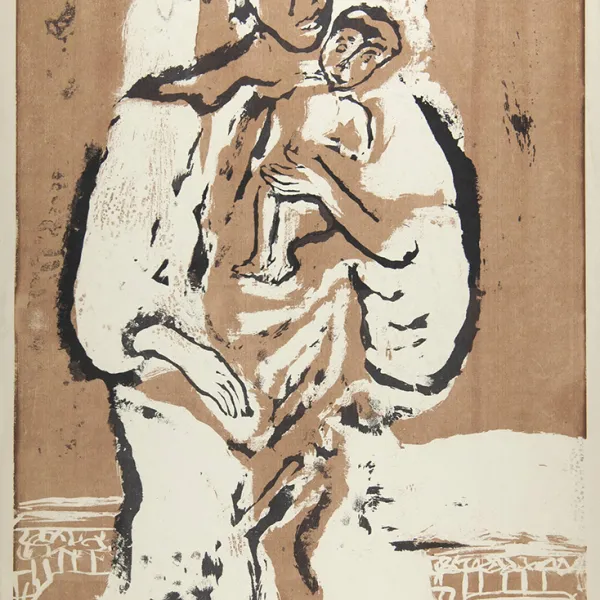

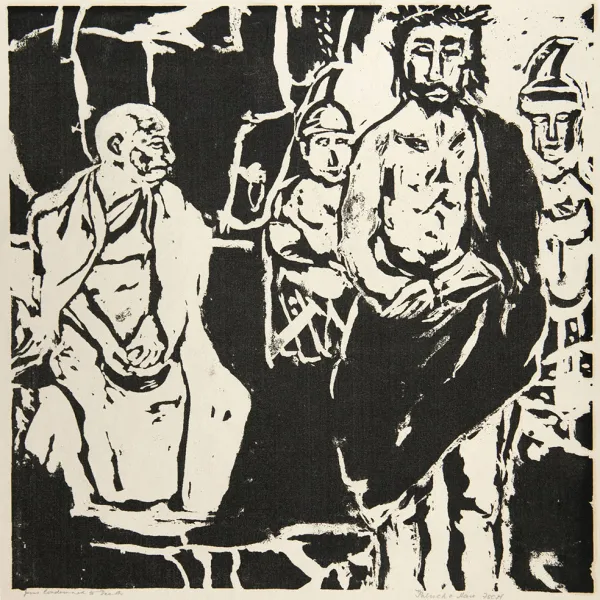

Just like Corita’s early works, many of the works in this show use as a foundation religious symbolism and scriptural references. In St. John the Baptist, an artist known as Semmion creates a rough and immediate version of the saint. Subtle areas of overlay, along with vivid color combinations, call attention to the bearded figure of Saint John. On the other hand, the artist allows for a lack of detail in the face and the form of the figure that gives him an abstracted, symbolic quality. The background of the image is an amalgamation of abstract forms in jewel-like tones, further heightening the sensory feel of the work as well exulting in the richness of the saint’s spiritual life.

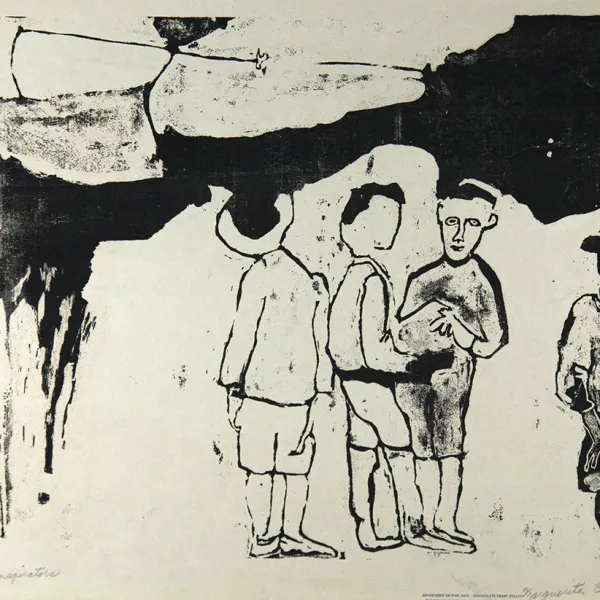

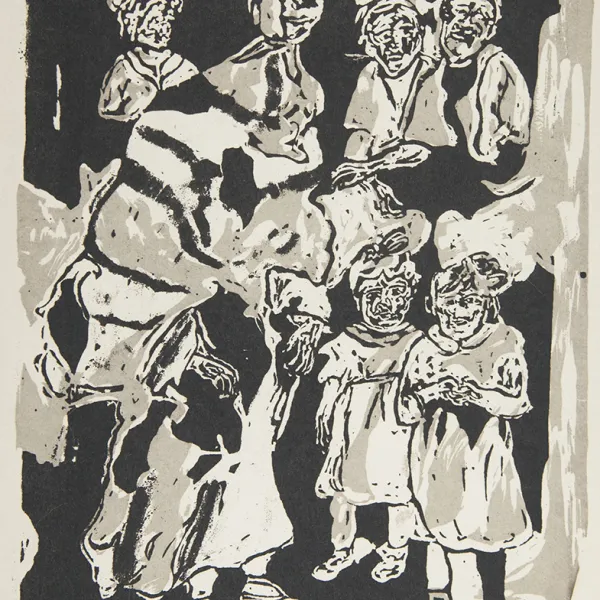

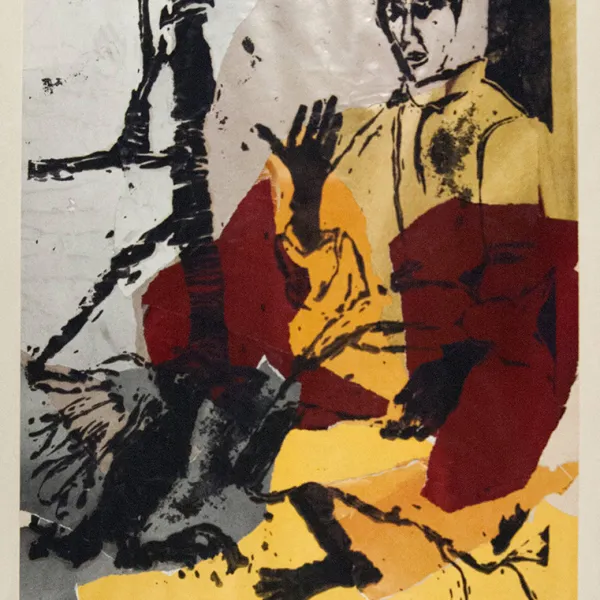

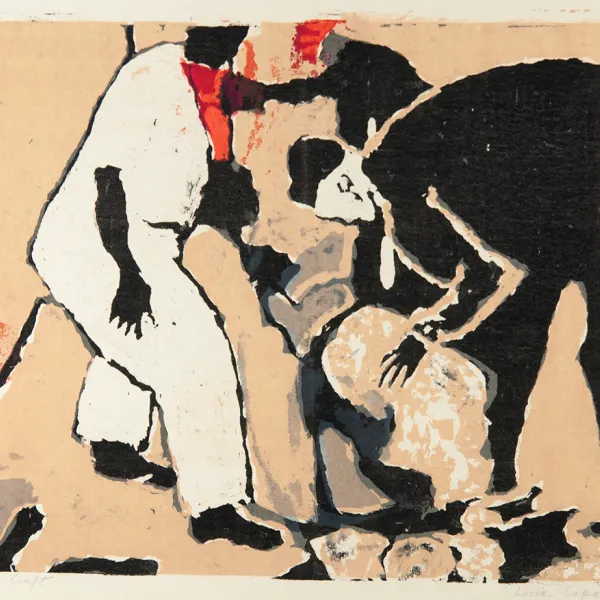

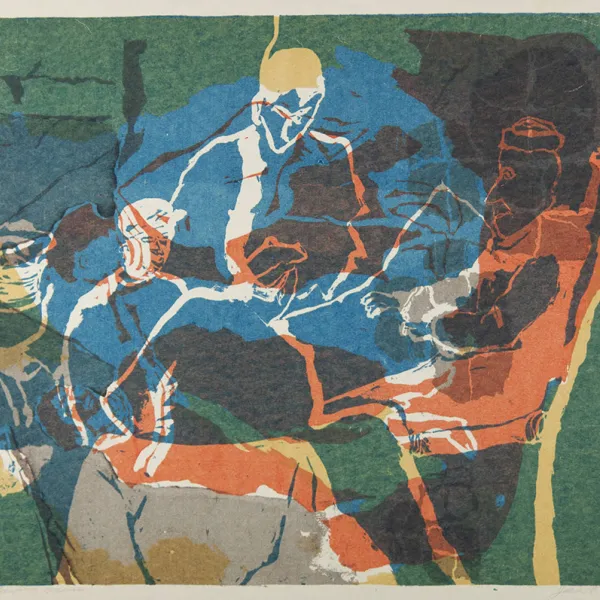

A work which seems to center on the concept of labor is that of Capacchione’s Loading the Craft, in which several figures can be seen lifting what appears to be a large parcel in the foreground. There is little definition given to the space around the figures to indicate their whereabouts, though the title indicates that they are loading some kind of craft, presumably a boat. All of the figures are faceless. The way in which Capacchione cuts off whole parts of these subjects and obscures them also seems to contain a political message, a sense that the workers’ identities are disconnected from their work.

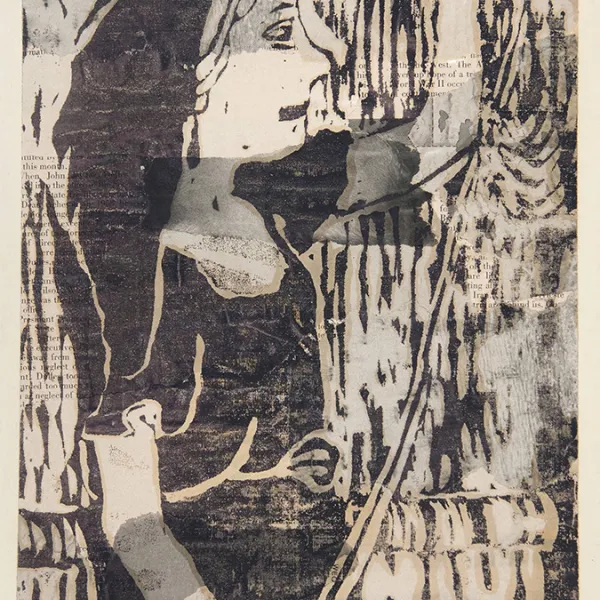

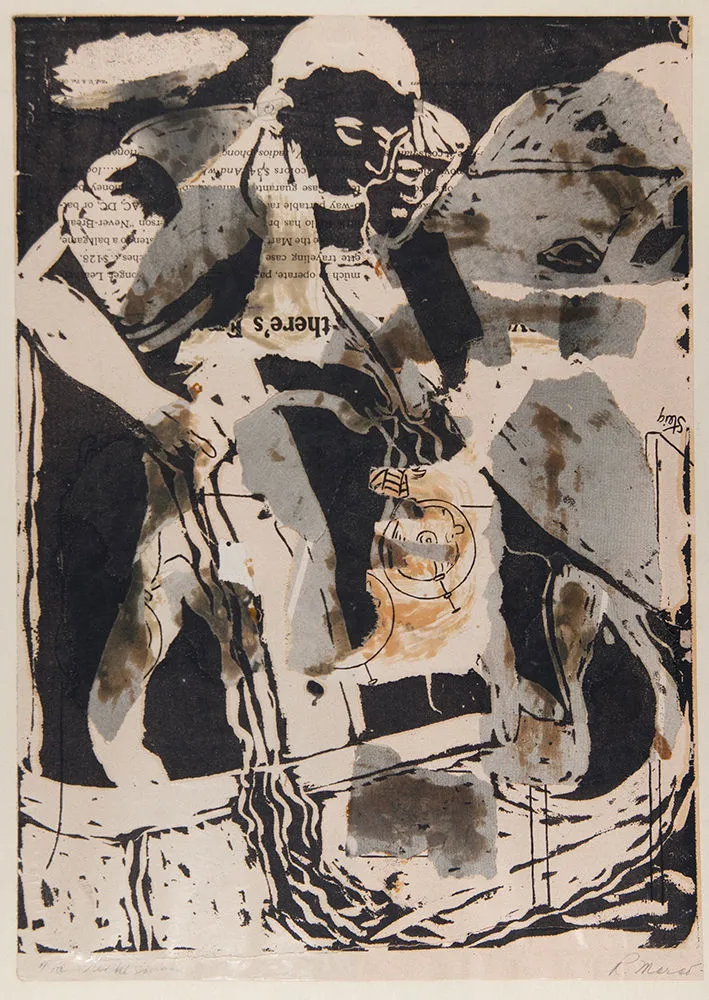

A work which simultaneously evokes the themes of religion and labor is The Fisherman by R. Mares. The central figure is simply rendered, his face open and his body leaning forward in the act of hauling in a fish. Was the artist’s intent humor, or perhaps hubris, with the addition of torn portions of a newspaper comic strip and a product advertisement, placed upside down within the composition? Since Christ is also said to have been a fisherman, the toiling, contemplative figure may also function as a religious symbol, a person set on slogging through a difficult task.

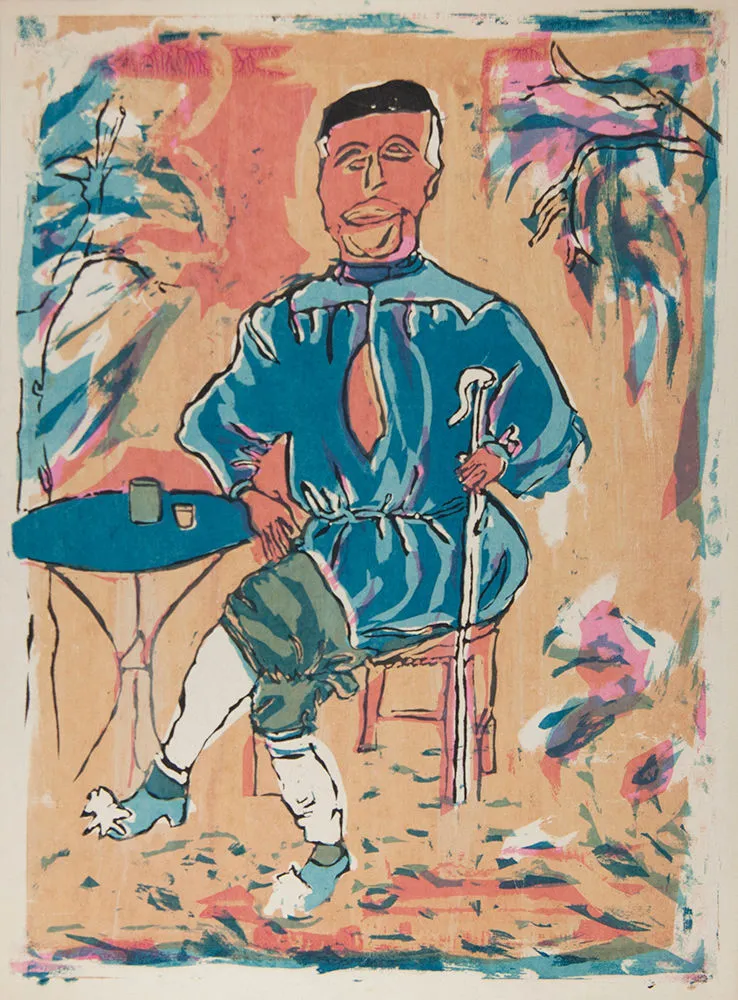

The concept of leisure is explored in several pieces in the show, including untitled [man seated at table], artist unknown. This accomplished work features an energetic line, uniform stylistic treatment, and a lively dance of pinks, blues, and blacks which help to communicate the casualness of the subject and even a certain cheeky savoir faire. The influence of an artist such as Picasso seems evident, both in the flattened, cartoonish style and subject matter, and in the ability to use such forms to capture the immediacy of real life.

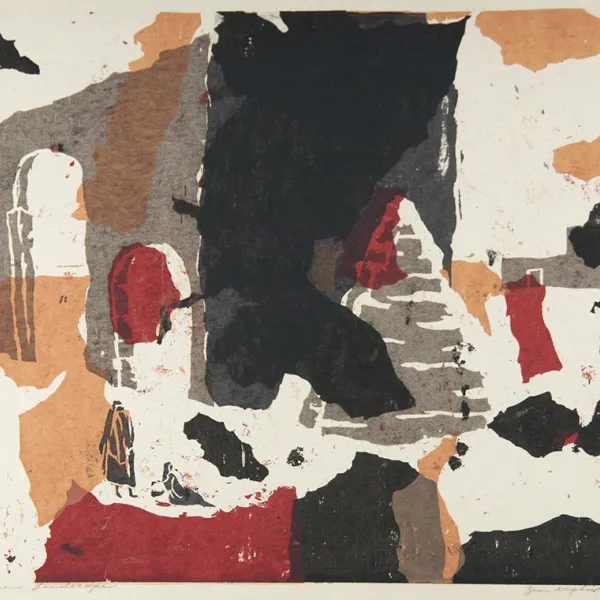

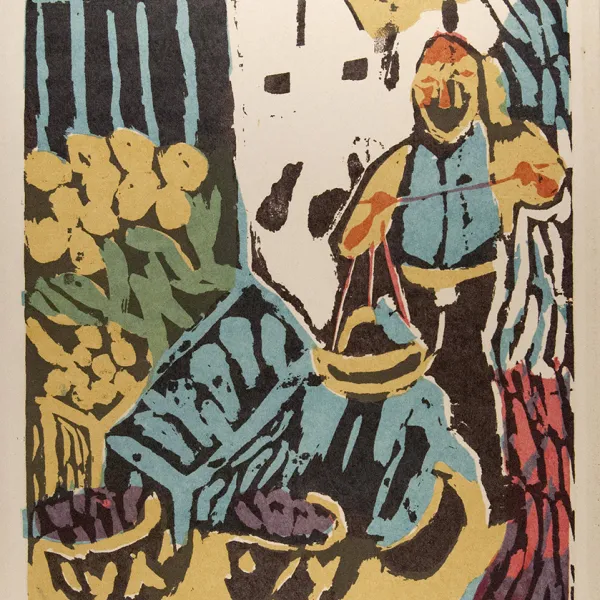

Another work which seems to riff on that of an established artist, namely Corita, is that of Sister Mary Ann Catherine’s Bethlehem. We can see strong similarities between it and Corita’s tobias. Both feature a multitude of intense colors that appear to vibrate on the paper, creating a lively, celebratory, feel. In both works the cacophony of colors may at first appear chaotic, yet each artist cleverly uses color to distinguish the elements within each scene and to create an overall flow.

As alluded to earlier, we are not sure how these student works became part of St. Kate’s Fine Art Collection. They languished for many years in the drawers of our collection, unseen by the public. So it is with much delight that we bring them back into the limelight so that you, the viewer, too, can take Corita’s advice to “look at this, and look again, and see anew.”

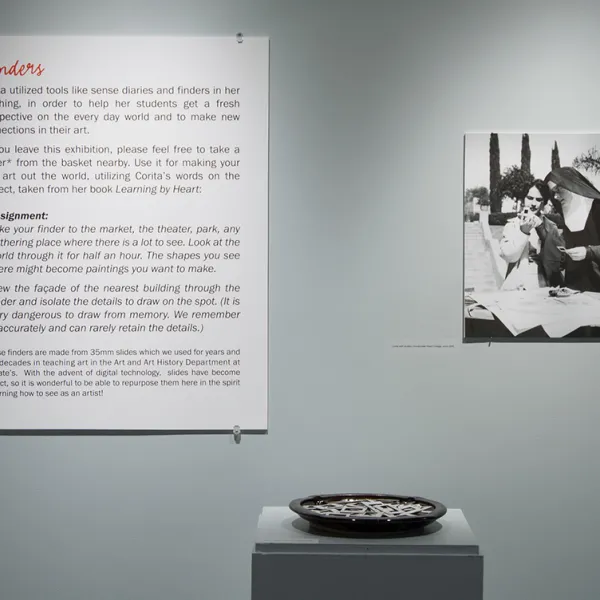

“Look at this, and look again, and see anew.”-Sister Corita Kent echoes the university’s efforts to digitize the permanent collection and expose the works to new audiences. Digitization allows us to simultaneously preserve a form of the art in our collection and share it with others. The digital collections can be accessed at http://contentdm.stkate.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/fineart

Image Gallery

Click an image to view in larger size

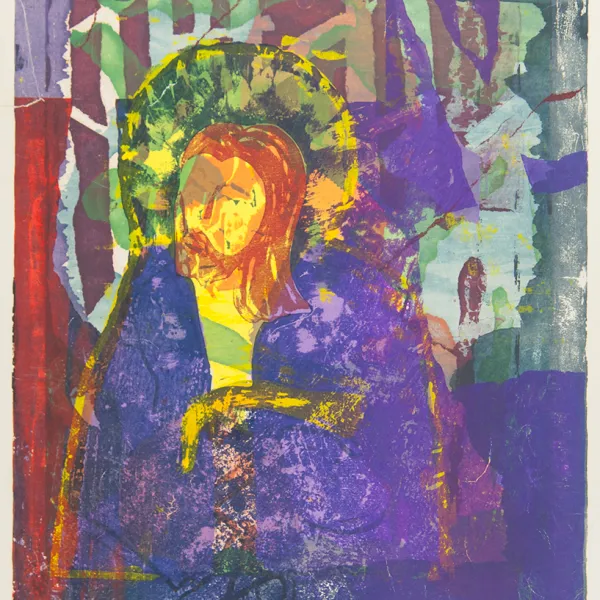

![untitled [Sweet it Was o Dear Heart…] Artist unknown, serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1210)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_1_1_600x600/public/2023-07/unknown-4.jpeg.webp?itok=hCJ5F0TS)

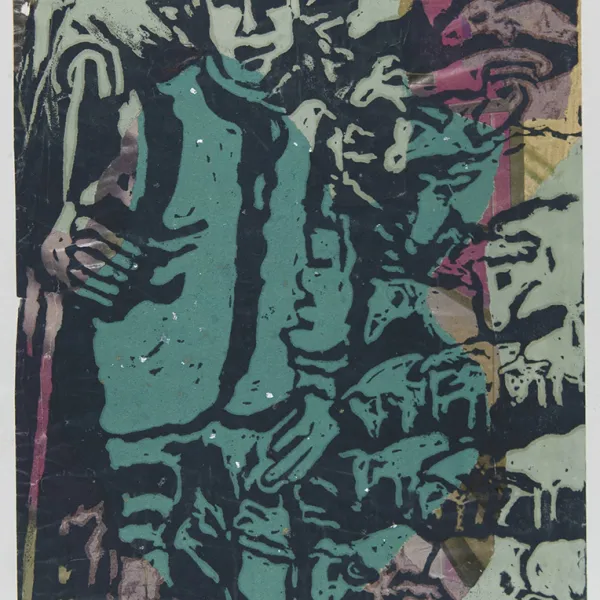

![untitled [Sweet it Was o Dear Heart…] Artist unknown, serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1211)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_1_1_600x600/public/2023-07/corita_unknown_artist_1.jpeg.webp?itok=bTbwUz_S)

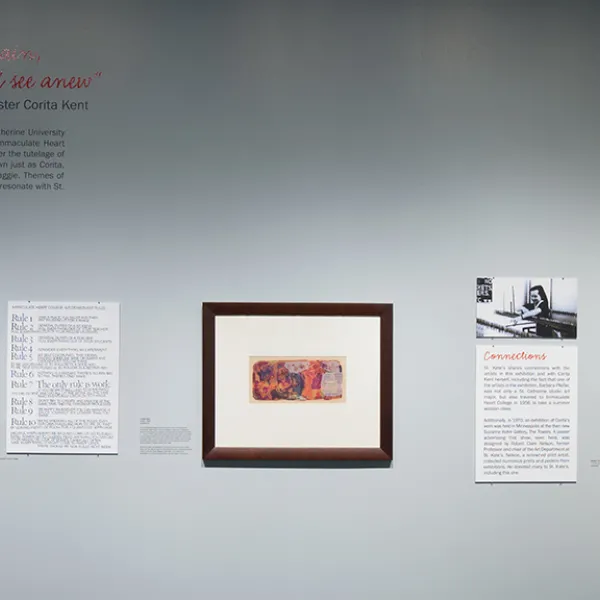

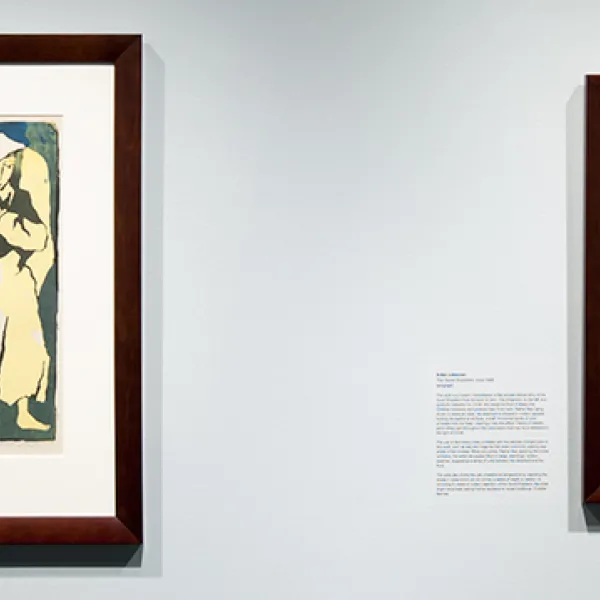

![installation view Artist unknown , untitled [Sweet it Was o Dear Heart…], serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1210 and 2013.0.1211)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_1_1_600x600/public/2023-07/corita_12.jpeg.webp?itok=YHGgCRh4)

![untitled [Man playing guitar] Artist unknown, serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1026)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_1_1_600x600/public/2023-07/man_with_guitar.jpeg.webp?itok=BzVL7evU)

![installation view Asba Jugle, untitled, print collage, 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.479), Lucia Capacchione, Loading the Craft, serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1278), Artist unknown, untitled [Man playing guitar] , serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent Collection (Accession No. 2013.0.1026), Artist unknown, untitled [Man seated next to table] , serigraph, circa 1956, St. Catherine University Permanent C](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_1_1_600x600/public/2023-07/corita_10.jpeg.webp?itok=a9ygUbWh)