November 7, 6 – 8 p.m.

Lecture and Gallery Talk: Saturday, November 7, 7 p.m.

All events are free and open to the public

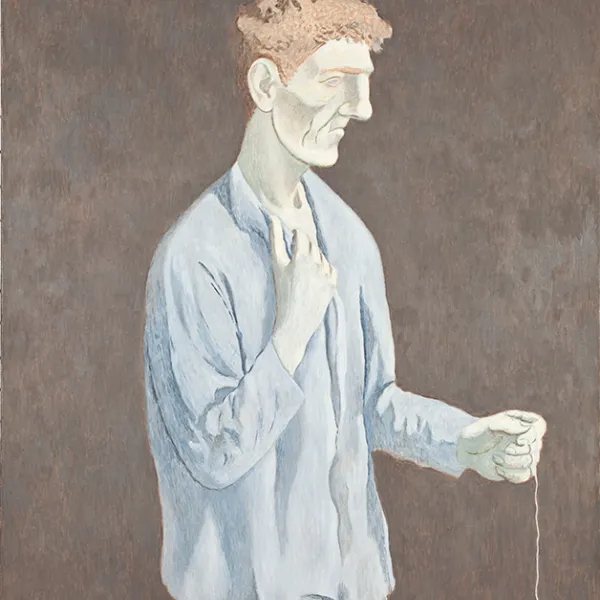

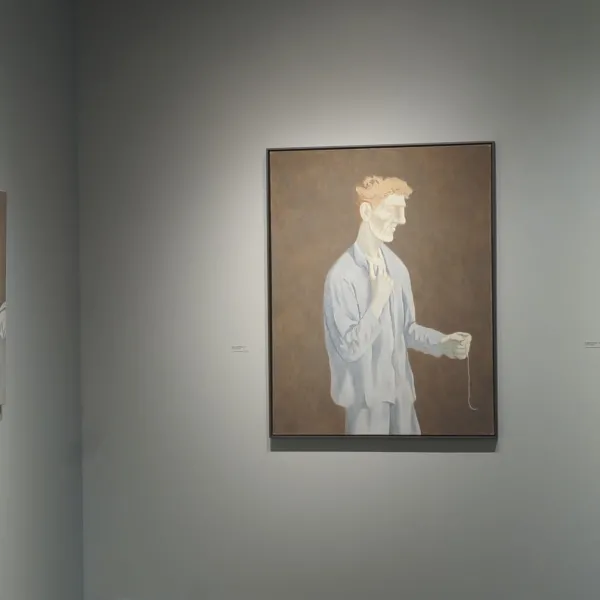

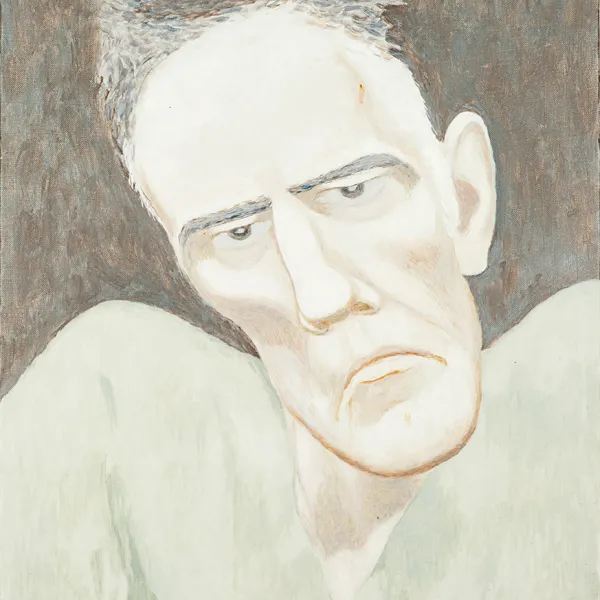

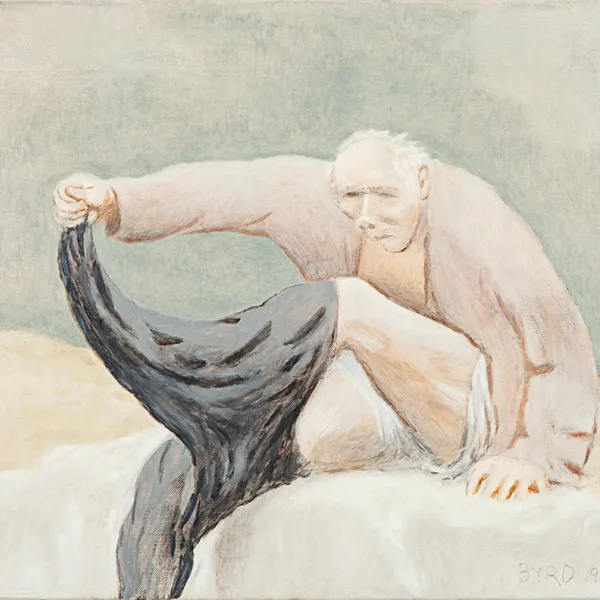

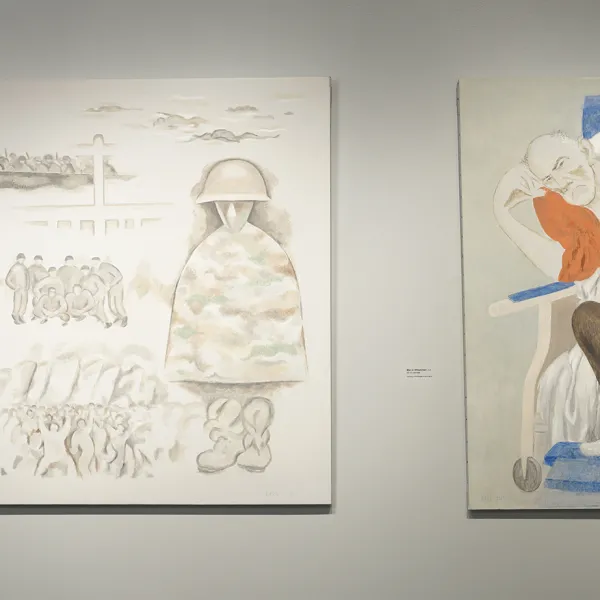

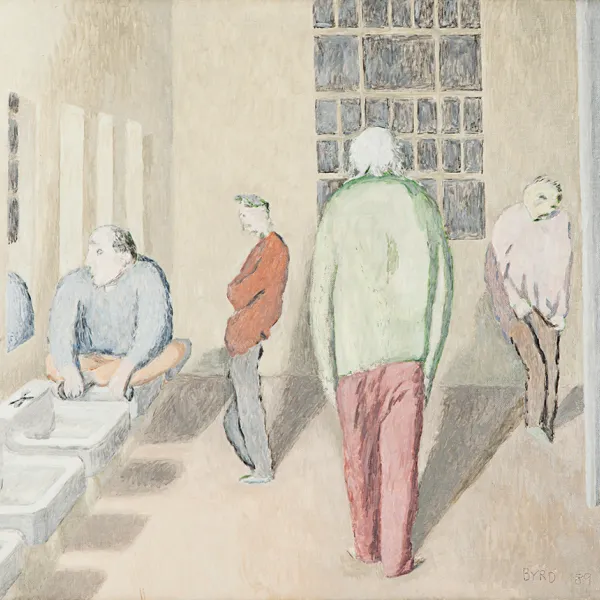

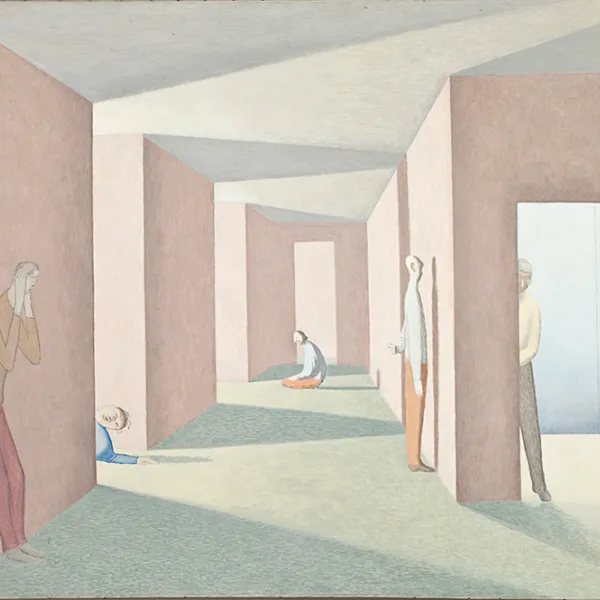

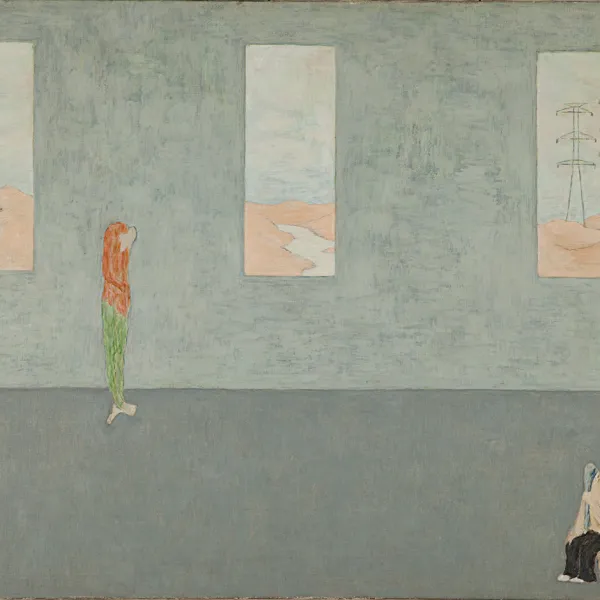

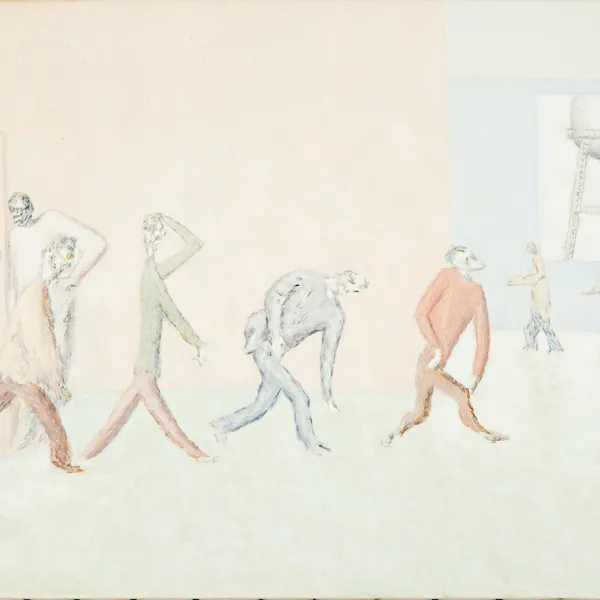

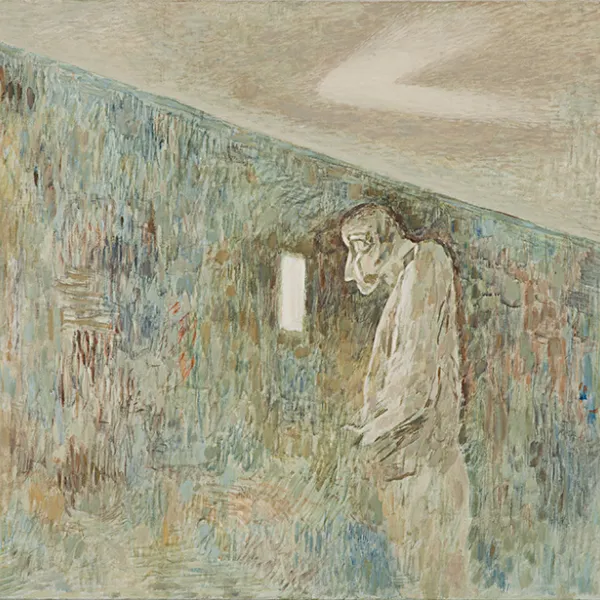

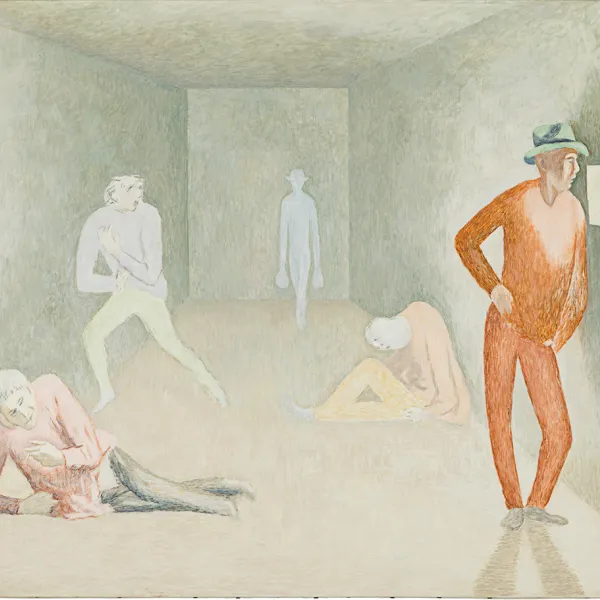

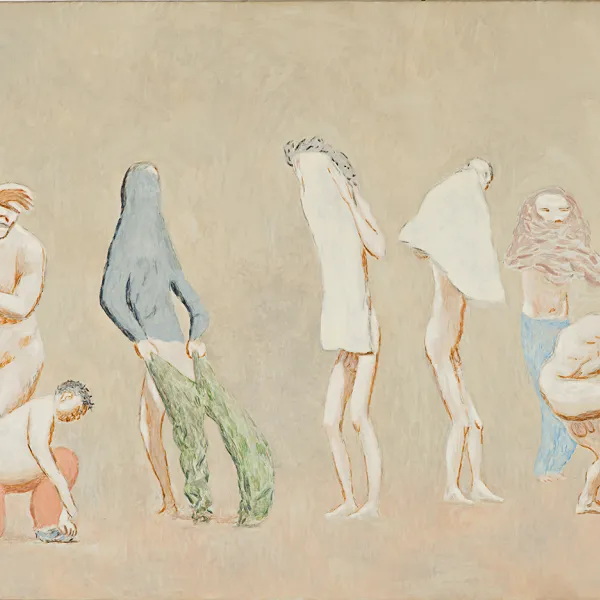

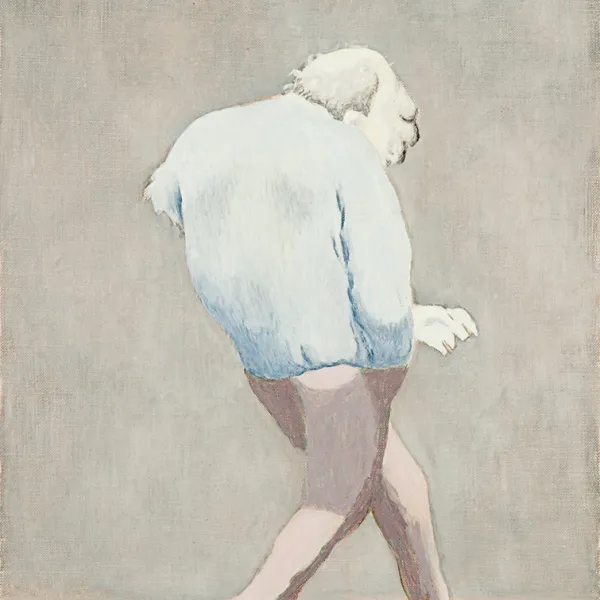

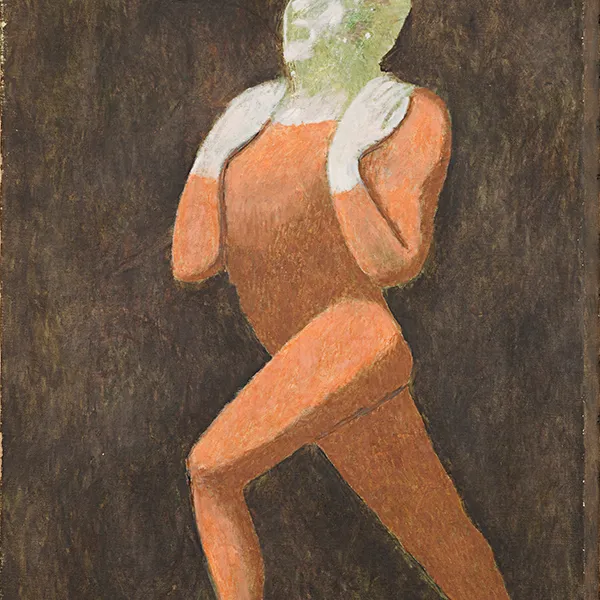

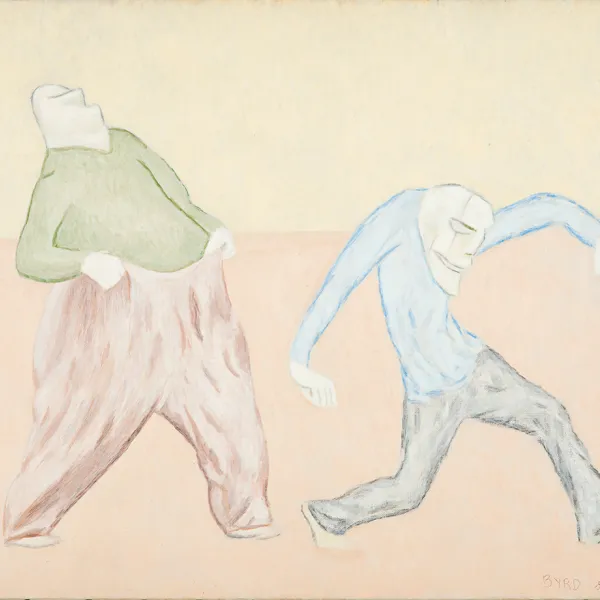

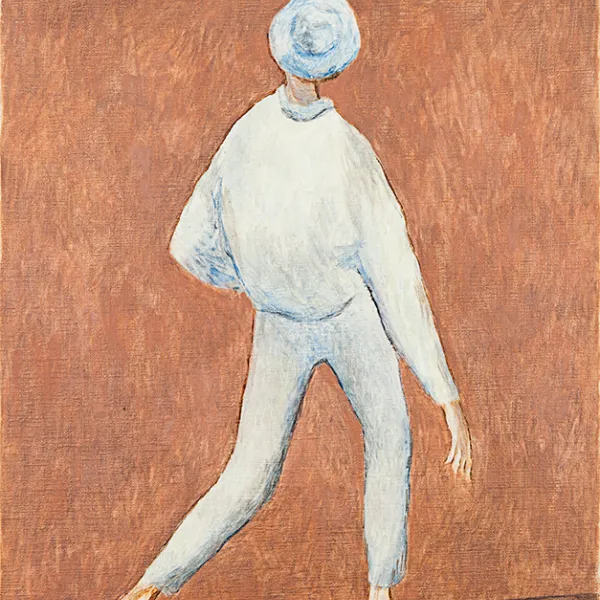

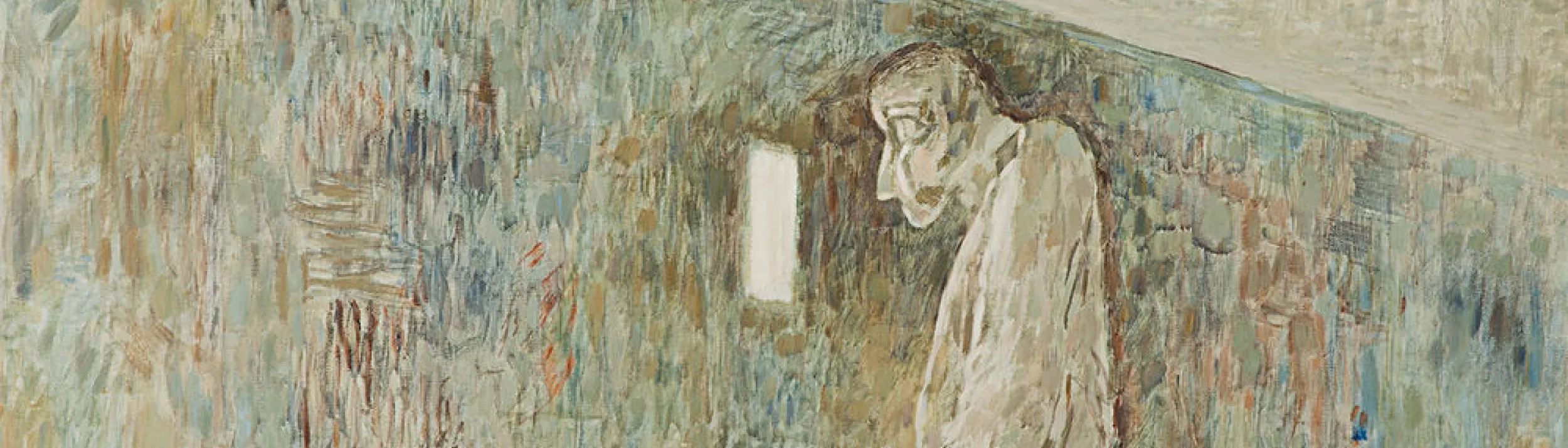

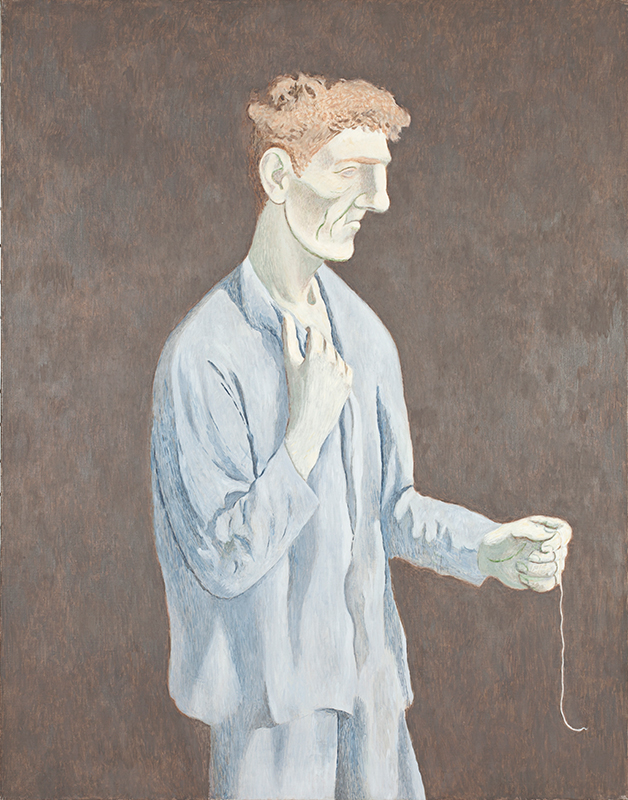

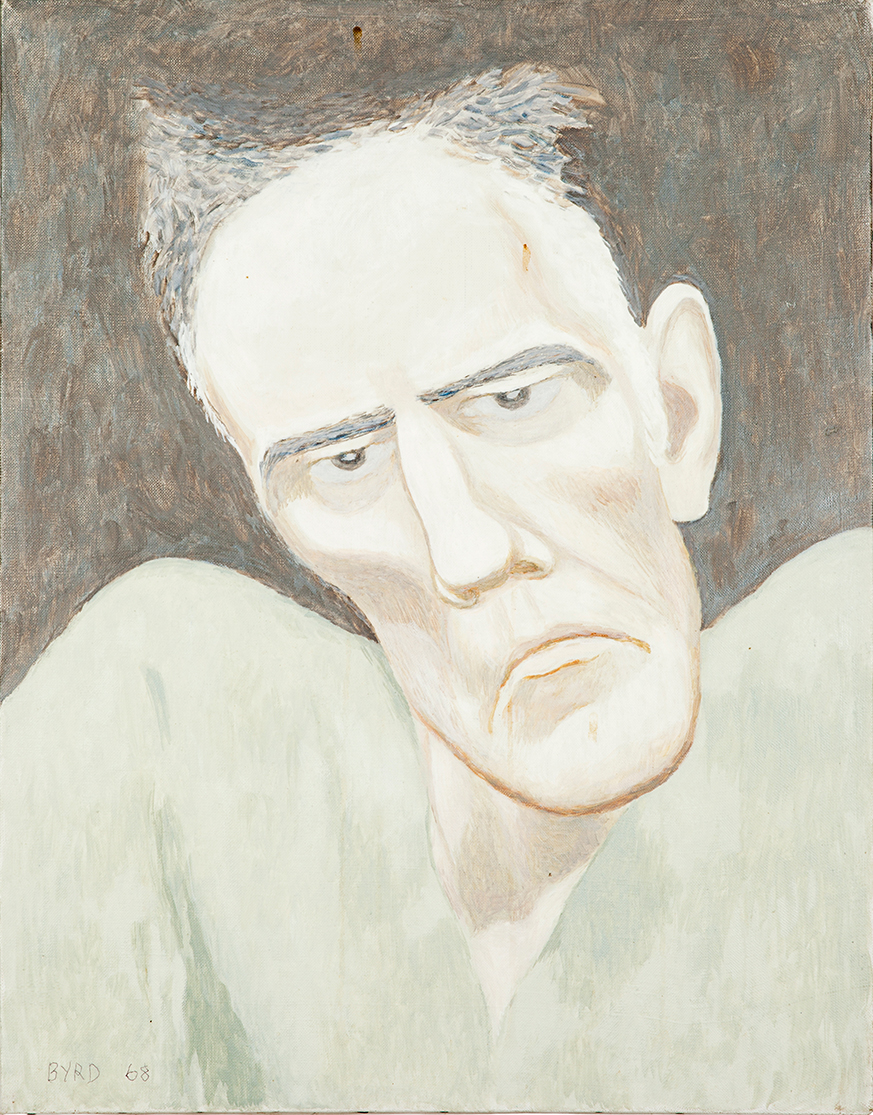

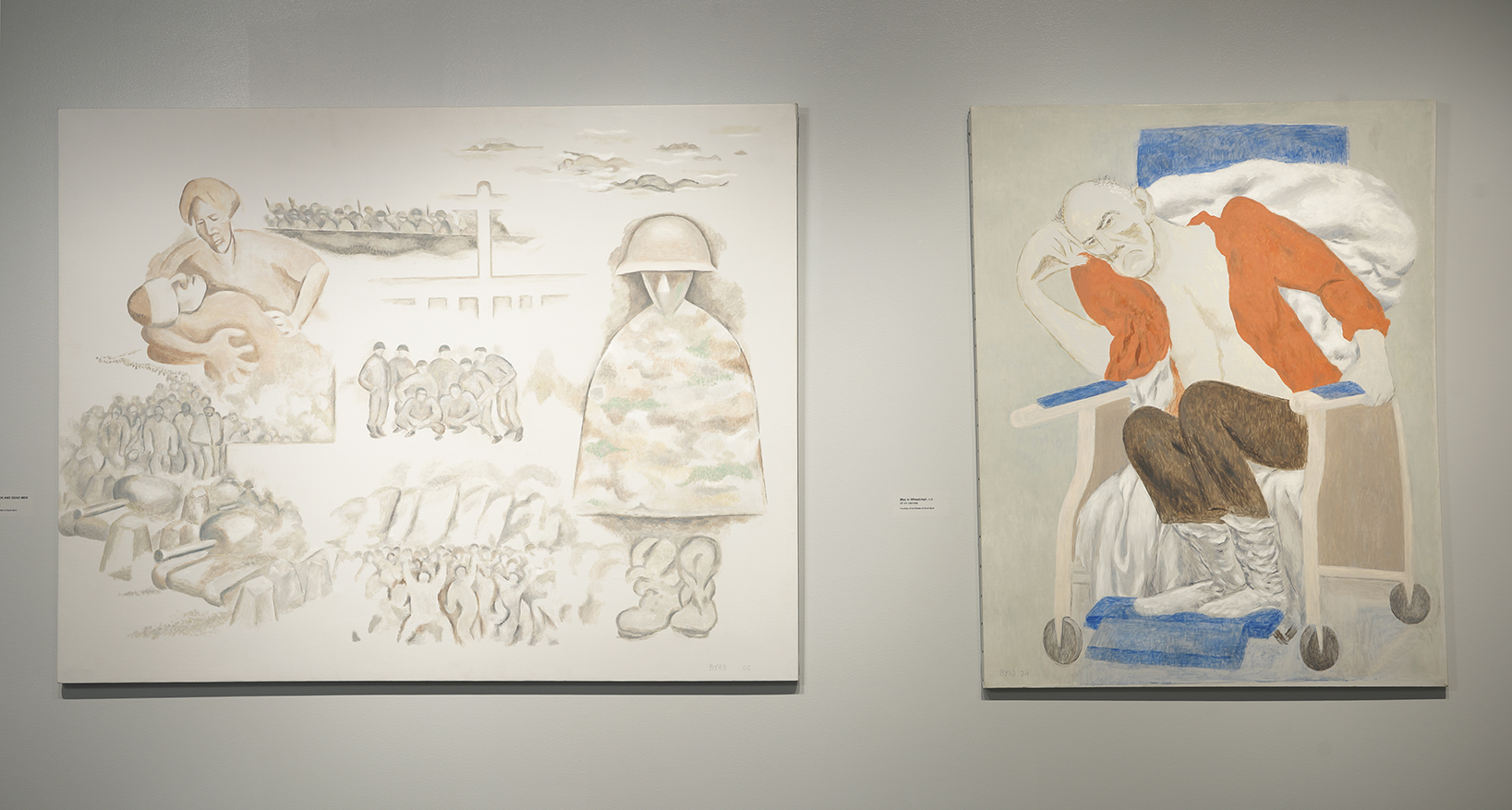

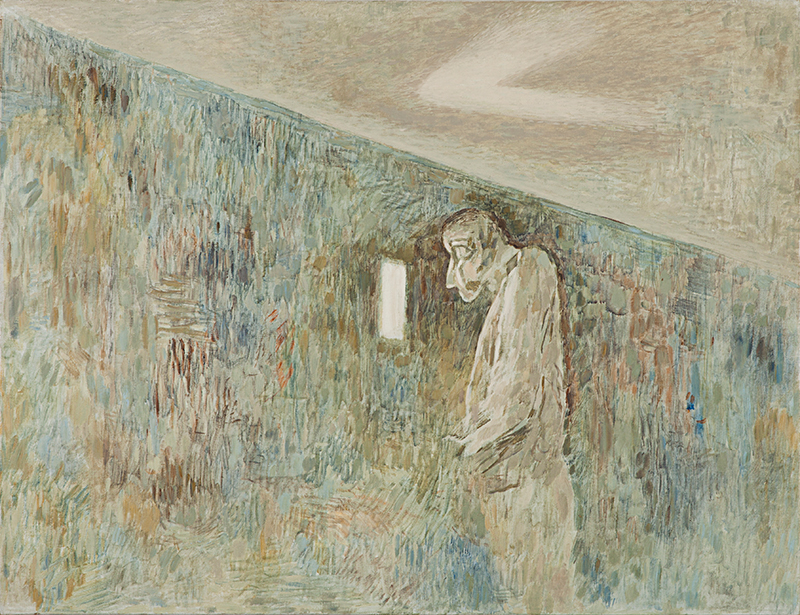

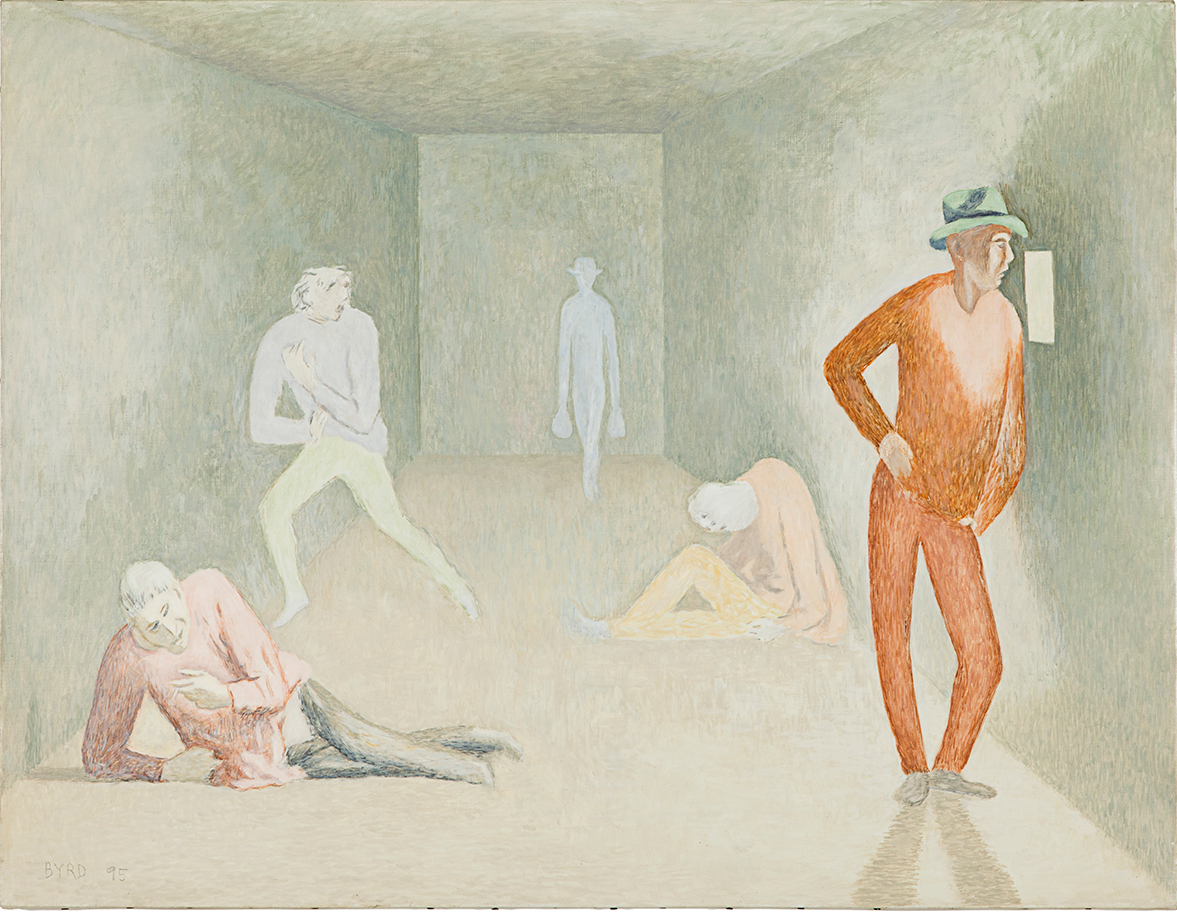

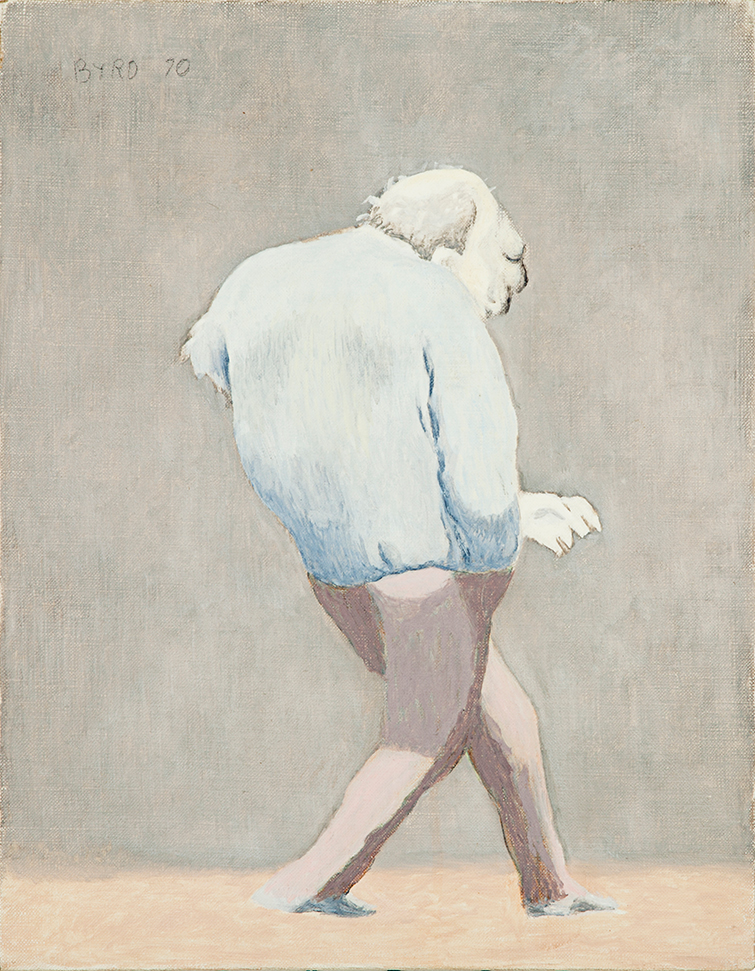

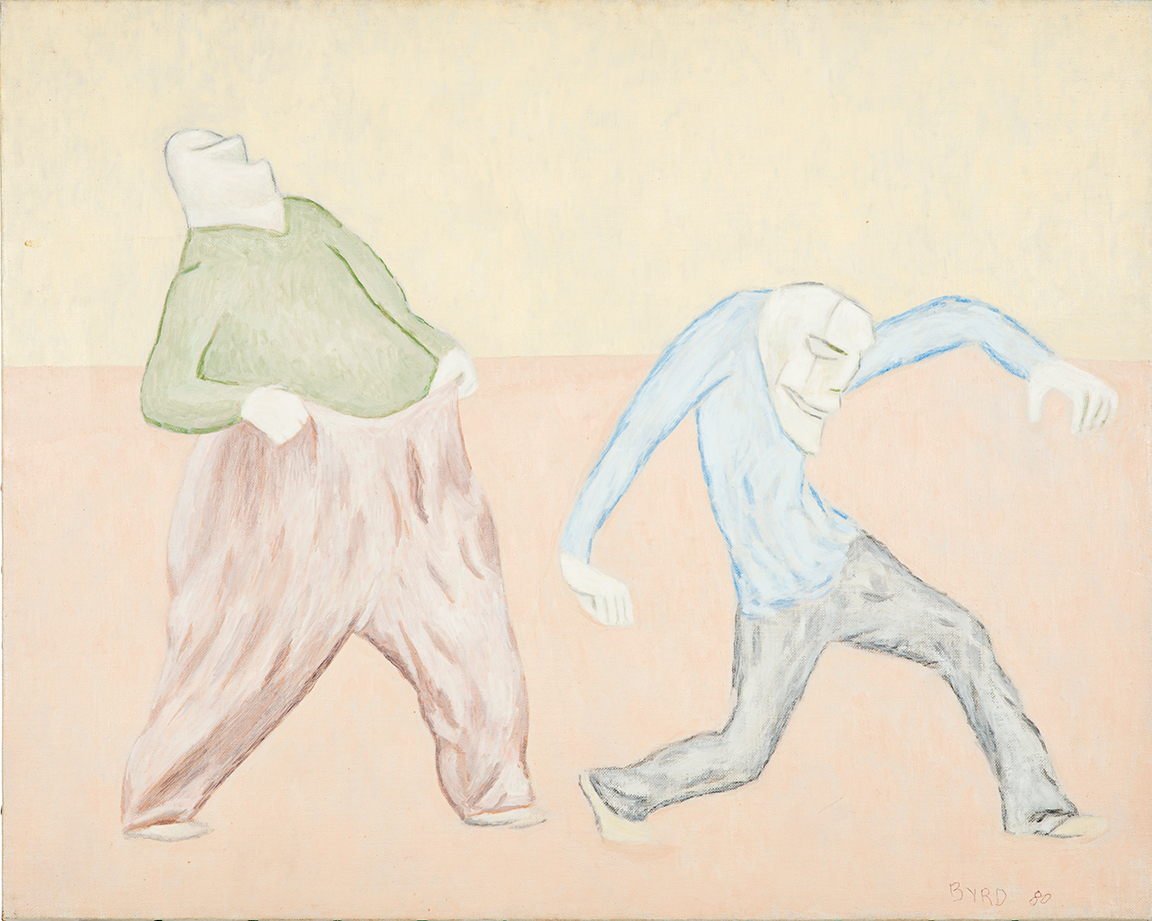

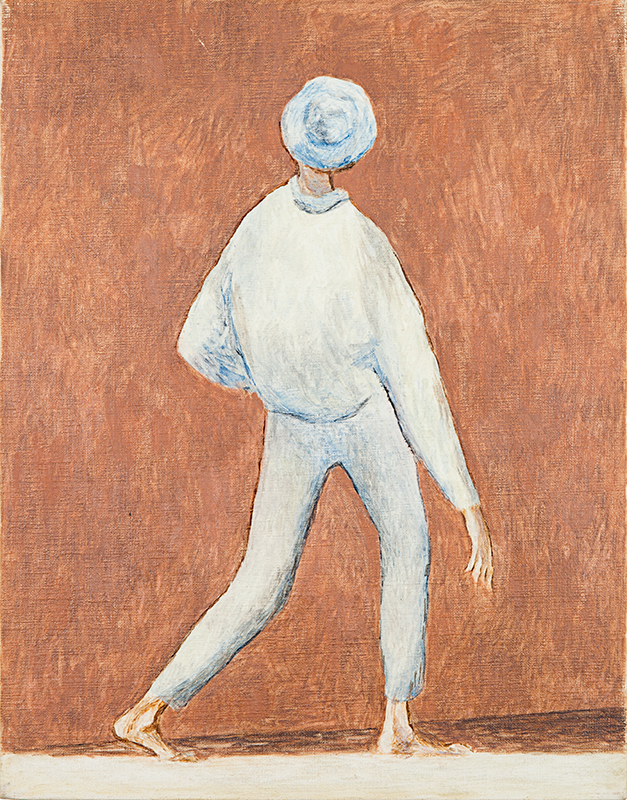

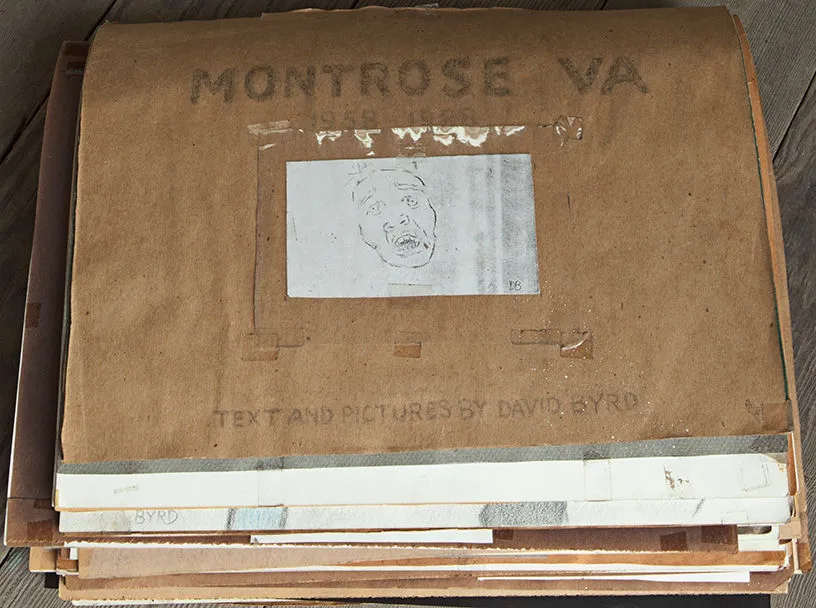

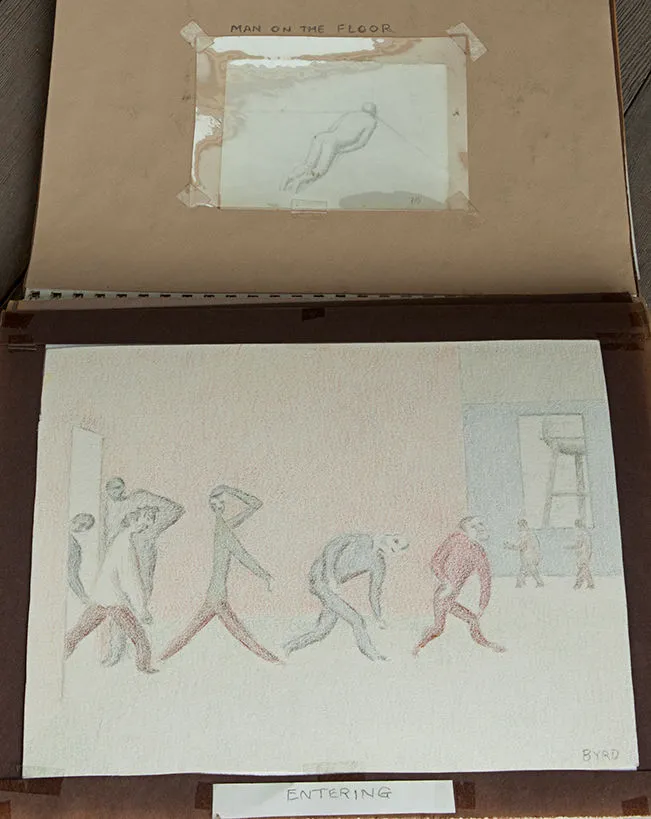

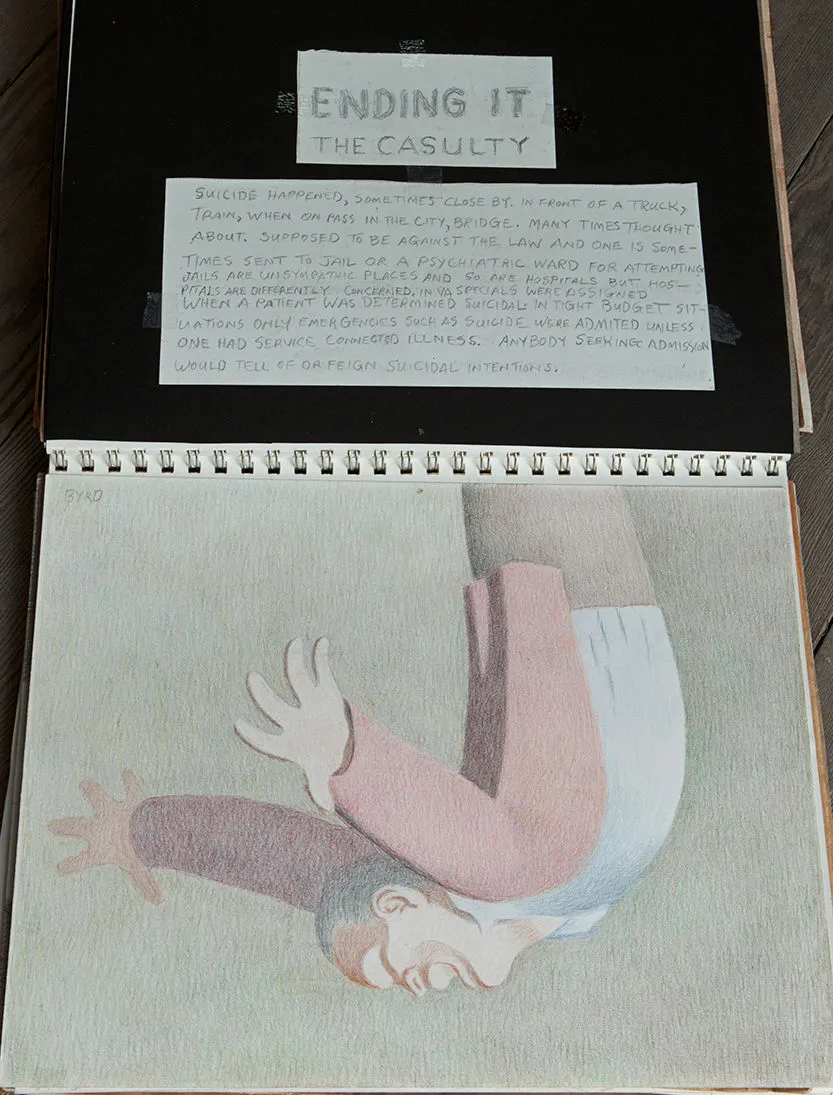

For 30 years, the late David Byrd worked as a night orderly in the psychiatric ward in a Veterans Administration Medical Hospital in Montrose, NY. The series of paintings illustrate the daily routines and individual personalities of institutionalized veterans. Byrd’s careful compositions reflect the isolation and desperation of mental illness, which few other artists have explored with such empathy and understanding.

This exhibition is concurrent with David Byrd/Peter Gallo at Zieher Smith & Horton, New York.

The Patients and the Doctors, November 19, 2015 – January 2, 2016.

Carol Lee Chase, Art/Art History Department Chair and Associate Professor

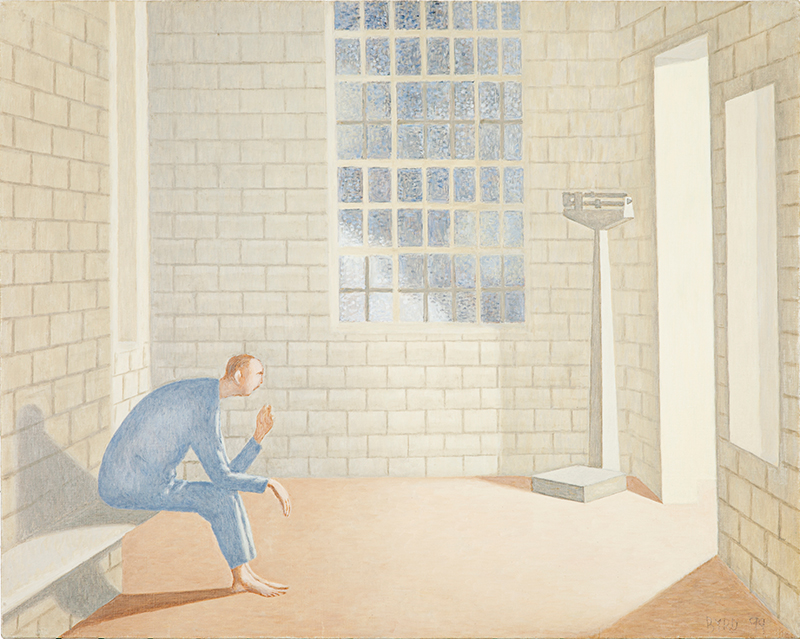

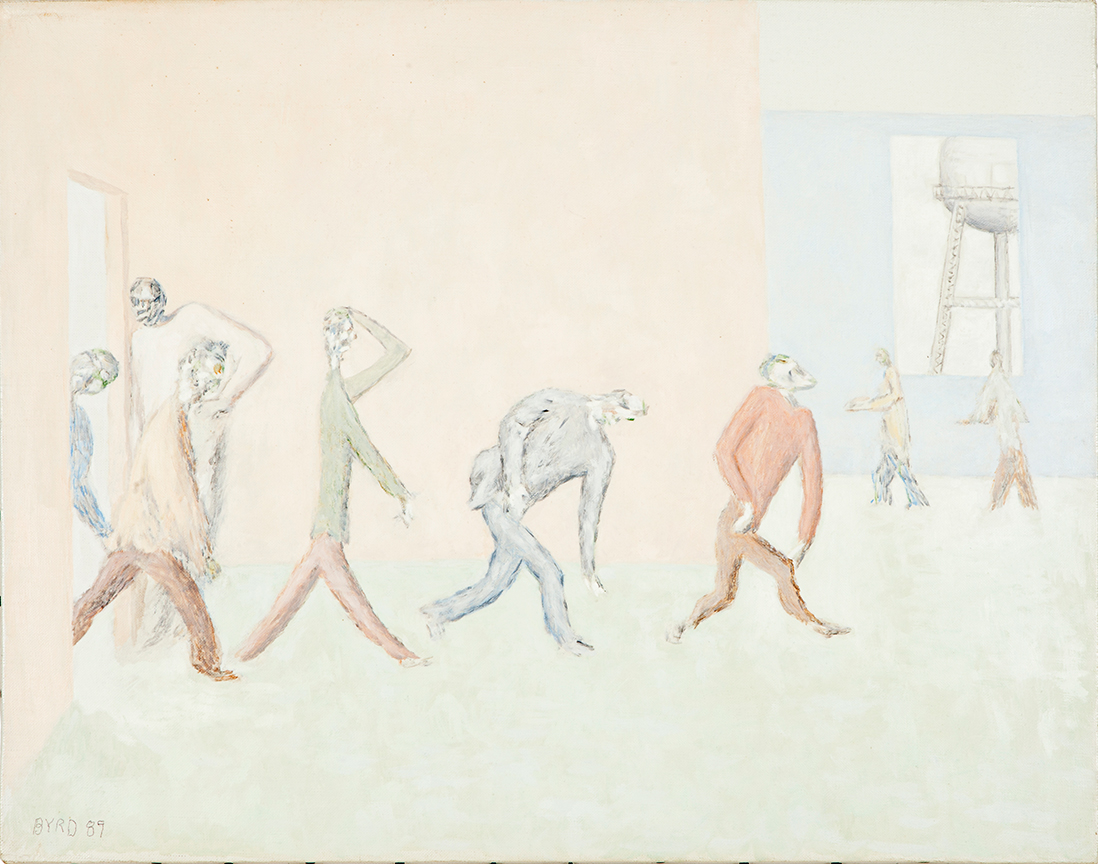

David Byrd’s paintings let us into a world that was once hidden deep behind walls. The institutions and mental hospitals of the past were bleak places where the mentally and physically handicapped were removed from society, often heavily medicated and basically locked away. David Byrd worked for 30 years in such a place: the Montrose VA Hospital in upstate New York. What distinguished him from the other orderlies is that Byrd was an artist; he was able to find great expression through his observations of the veterans that were housed in this oppressive and discouraging environment. He had the artistic ability to capture the essence of their lives as they struggled through their days in the isolation of the institution’s hallways, bathrooms and waiting rooms.

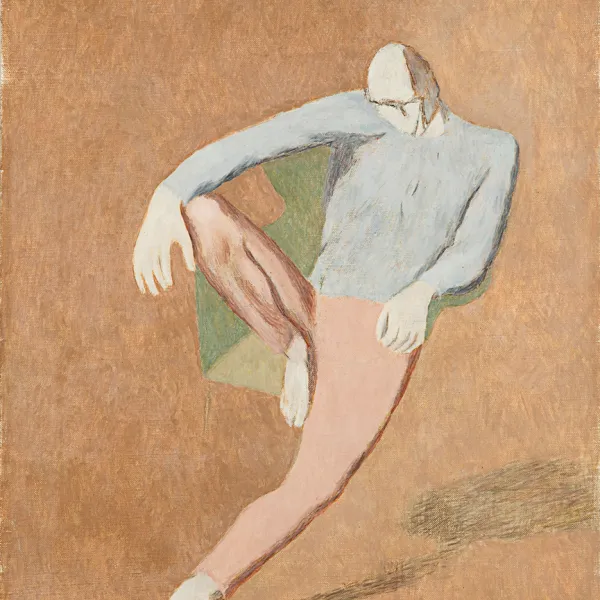

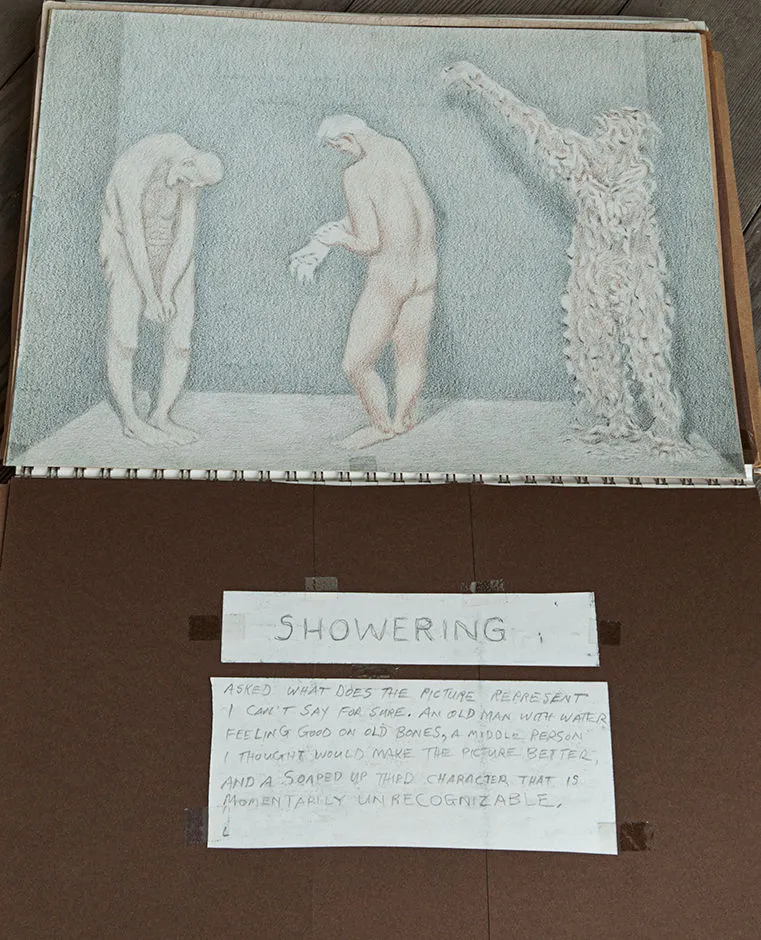

The paintings in this exhibition illustrate Byrd’s empathy and understanding for these veterans. Byrd captures their pain and disassociation through their body language. Each individual has their own distinct movement or pose. It’s difficult to look away from the concentrated effort of pulling off one’s trousers or trying to figure out what to do in a hallway. The paintings are portraits of men in all stages of undress and vulnerability. Even one’s bed sheets become a battleground of distress, confusion and imprisonment.

Byrd uses a high key range of color. His darks are mid tones and the overall effect portrays a bleached out, fluorescent environment. There are no darks and brooding shadows in which to hide. We see everything. His brushwork is active, it flickers over the surface of the painting. The compositions are strict like the architecture of the interiors. People are often silhouetted against vast neutral walls and spaces, while others are confined in geometric mazes. All of these strategies add up to a powerful yet delicate painting style.

My good friend and colleague, Jody Isaacson, introduced me to David Byrd’s paintings. We are fortunate to have this exhibition here at The Catherine G. Murphy Gallery. Please take the time to look at Byrd’s sketchbook and to watch the video that features David Byrd in his home.

Many thanks to:

-the staff of The Catherine G. Murphy Gallery:

Administrative Assistant Ann Buchen,

Gallery Technician Kimberlee Roth

and Gallery Director Kathy Daniels for their patience and expertise in installing exhibitions

-The CGM Gallery Committee and my colleagues in the Art and Art History Department

-David Wells, Gallery Director at Edgewood College in Madison, WI for transporting the work here

-The Estate of David Byrd for providing us with the opportunity to exhibit the paintings

-and kudos to Jody Isaacson for discovering David Byrd. May his memory live on through his paintings.

David Byrd was born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1926. His father, who suffered from mental illness, left the family when David was a young child. When David was twelve, his mother was forced by economic hardship to abandon him and his five siblings to foster homes. During the next four years, the children lived in three foster homes. A number of David’s paintings document this period of upheaval in his life.

In 1942, David’s mother gathered her children back to her. Working as a ticket seller at a movie theater in Brooklyn, New York, she could barely support them. David had shown artistic ability from an early age, but she was forever worried about money and pressured him to find suitable employment rather than pursue his artistic side.

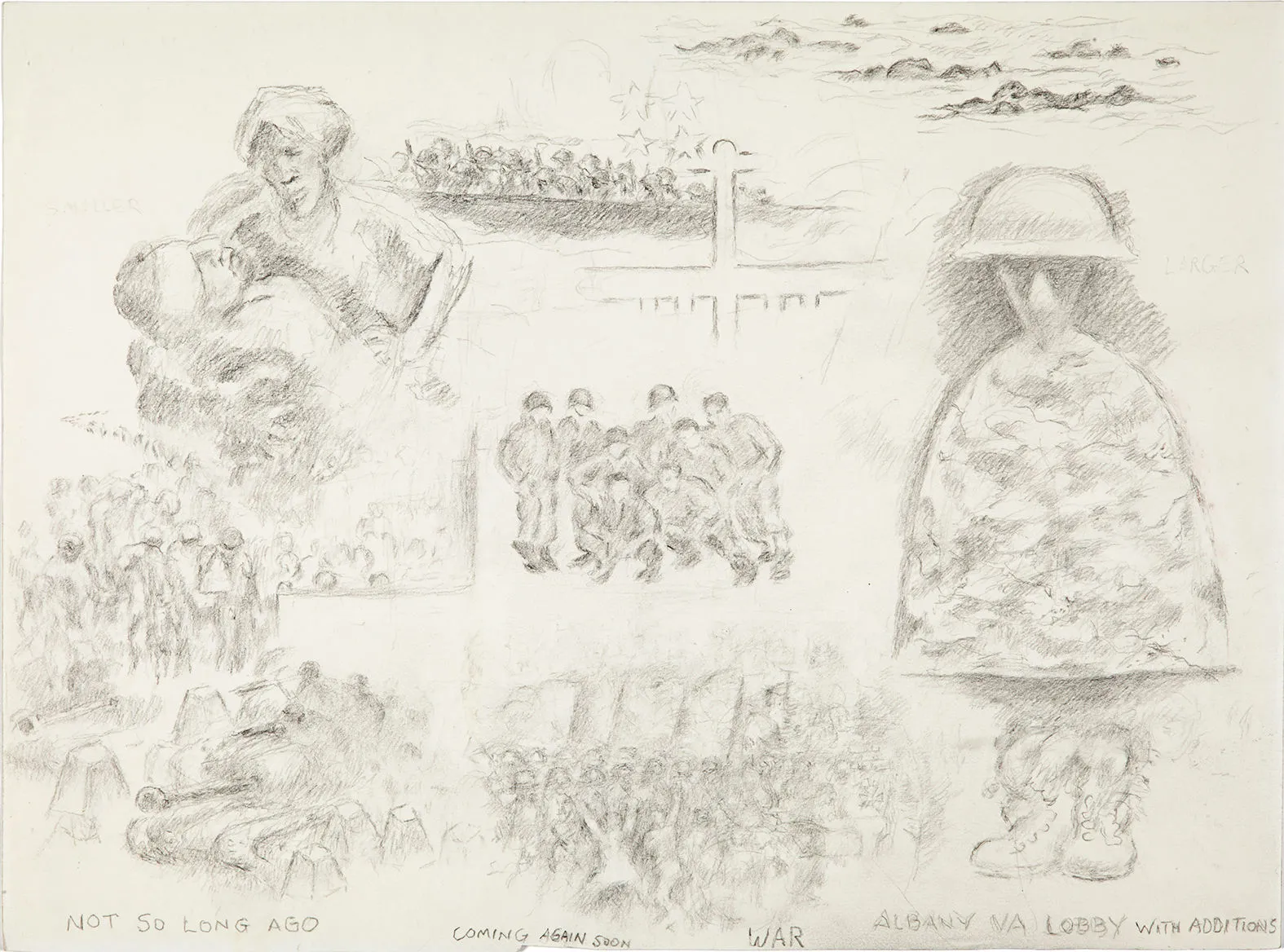

At seventeen, he joined the Merchant Marines and traveled through Europe, the Mediterranean and Asia before being drafted into the U.S. Army as an artillerist. During this time—World War II—he filled sketchbooks with maritime-themed drawings, and portraits of his fellow sailors and officers.

After the war he studied briefly, through the G. I. Bill, at the Dolphin School of Art in Philadelphia. He continued his studies for two years at the Ozenfant School of Fine Arts on the Lower East Side in New York City. (Amédée Ozenfant was a Parisian painter, influenced by Paul Signac and Le Corbusier, and immigrated to the U.S. in 1938.) Though David did not become a disciple of Ozenfant, one can sense his formality in both composition and sophisticated color relationships. Ozenfant was the most influential mentor in his life.

Throughout the 1950s, David lived in various parts of New York State working odd jobs, mostly low-status positions that allowed him time to paint. He was a deliveryman, janitor, liquor store clerk, movie house usher and, on Coney Island, bartender at a resort. Many of his genre-scene paintings came from this period of listlessness.

In 1958, David took a job as an orderly in the psychiatric ward at the Veterans Administration Medical Hospital in Montrose, New York. For the next 30 years, he worked with doctors and nurses in care of patients whose damage resulted from World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. This experience provided him with his defining body of paintings, which related to the patients and their individual behaviors, general routines and distinct personalities. He also painted scenes from his daily commute—views of bridges, waterways, mountains and the regional landmarks of filling stations, cafes and shopping centers.

In 1967, David married Shirley Silverman, a nurse at the V.A. They had a tumultuous relationship that ended in divorce ten years later.

In 1988, at age 62, David retired from the hospital. He purchased 11 acres in Sidney Center, New York, a small hamlet in the Catskills. For four years, he lived in a hunter’s shack while building the stone foundation for his home. An avid scavenger, he salvaged many of his home’s architectural details from abandoned structures. He was also an active bottle collector, attending auctions and shows during this time.

By 1994, with his house more or less complete, David devoted himself full time to painting—largely from memory—the people, places and situations from his past. He also began a series of wood sculptures, some combining found objects, some composed of large wood blocks carved into life-size figures.

A chance meeting with a neighbor in the fall of 2012 led to David’s first professional exhibition seven months later. He was 87 years old. David Byrd – Introduction: A Life of Observation at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle, Washington, featured 85 paintings, three sculptures and numerous drawings. By the end of the exhibition most of the work had sold. Finally David received the recognition that had eluded him all his life.

Just days before the Seattle show opened, David was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. Despite failing health, he was able to take his first airplane ride and attend the opening. His gallery talk was one of the best attended in Kucera’s history.

On May 30th, 2013, David Byrd died surrounded by friends at the New York Veterans Home in Oxford, not far from his home in Sidney Center.

This video features the painter David Byrd with Jody Isaacson at his home and during the first public exhibition of his work. This was recorded by Andrea Hull and was published February 11, 2013. Please visit the David Byrd Estate's website at www.davidbyrdestate.com

Image Gallery

Click an image to view in larger size