November 2, 5-7 p.m.

ARTIST BIO

Artist, teacher, curator and parent Linda Brooks was born in Brooklyn, NY, and has made the Twin Cities her home for more than 40 years. Throughout most of her photographic practice, she has explored concepts around family. The content of her imagery is personal, yet she remains conscious that family can be relative to one’s identity and include larger cultural contexts. Her interest in representing particular individuals, scenarios or objects is prompted by the proximity of relationships, experiences and external circumstances explored in many of her photo-based projects. Some of these projects include portraits, it was the sound of the ocean, between the birthdays, teens, lifecycles, and lifecycles objects.

In addition to being a 2018-2020 Hermitage Fellow, Brooks has been granted fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Minnesota State Arts Board and the McKnight Foundation. Her photographs have been included in more than 80 group exhibitions at venues such as Pier 24, San Francisco, CA; Aperture, New York, NY; Hallwalls, Buffalo, NY; and the 5th Vienna Biennale, Austria. She has had solo exhibitions at the George Eastman House, Rochester, NY; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; the Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; and the Sabes Jewish Community Center, Minneapolis. Brooks’ photographs are in the collections of The Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Minnesota Historical Society, George Eastman House and The Brooklyn Museum. Young Voices: photographs of/by girls/teens/women, and the Jerome Hill Centennial Photography Exhibition 2005, are among the many shows she has curated. A selection of images from between the birthdays are included in the anthology, Reframings: New American Feminist Photographies. Her first monograph, PROXIMITIES: art, education, activism, is forthcoming in 2020. Brooks earned her B.F.A. (1973) and an M.F.A. (1976) from the State University of New York at Buffalo. Photography projects can be viewed on her website: lbrooksphoto.com

ARTIST STATEMENT

This body of work, lifecycles objects, is a progression of ideas that I have worked with for nearly four decades. Beginning with the series it was the sound of the ocean, from 1980-81, I began photographing objects belonging to my grandmother and me that acted as catalysts for memories of past experiences and current thoughts about our lives. These fabricated scenes were synthesized from reflections about my relationship with my grandmother, who at the time was living with Alzheimer’s.

Concurrently, I was also interested in photographing relatives, neighbors in South Minneapolis and friends in ways that emphasized relationships and situations in the present time. This series, titled portraits, started with photographs of my grandfather, alone, in his Brooklyn apartment.

For much of my photographic work, the titles and extended texts provided a context for the image—a place, a time, a relationship, a bigger story, a history, a life, an event, a cultural practice, a ritual, an activity. I continue to frame the image in a literal and expansive way, adding to the significance of the image.

As I work on my projects, I am conscious of my identities as a white, middle class, heterosexual, Jewish, woman and how that has affected my experiences in the world. My perceptions and attitudes are enmeshed in the work. My personal narrative is entwined with the societal context of the images and in the writing.

From 1983 to the beginning of the 2000s, the extended personal documentary, between the birthdays, used narratives and images to focus on contemporary family dynamics and dilemmas while raising a family amidst complex cultural issues. I noticed how family, on a large and minute scale, is a repository for the ways in which our culture collides. However, the photographs and texts imply a consciousness that suggests dialogue where the family can also be a place of resistance and change.

The teens project began in the late 1990s when my two children were teenagers, and I was teaching high school students. We used a collaborative process where the teens most often participated in determining their body language, facial expression, clothing, location, and final image. The teens played an important role in defining themselves and were represented in the contextualization of the images and their own words.

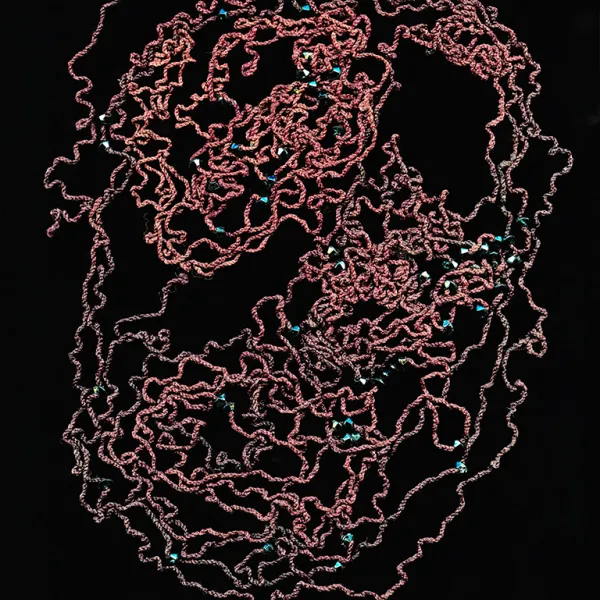

For nearly forty years I have been collecting images and objects from four generations of family members. The known, maternal family history dates back to the 1907-10 immigration of my great-grandparents and grandfather from Zhlobin, Belarus (formerly Russia) and the lives they led in New York during the 20th century. Over the last eleven years I have used this archive to construct several series for the lifecycles project. I explore how individuals’ lives intersected with others; popular culture, historic and political events, technology, and lifestyle choices are part of this exploration. By enlarging the context of photographs with limited information, I am seeking a deeper understanding of the ambiguous personal histories and emotional realities left behind. Some of the imagery relates to Jewish immigrant situations and anti-Semitic sentiments in this country, while other composites parallel a backdrop of World War II.

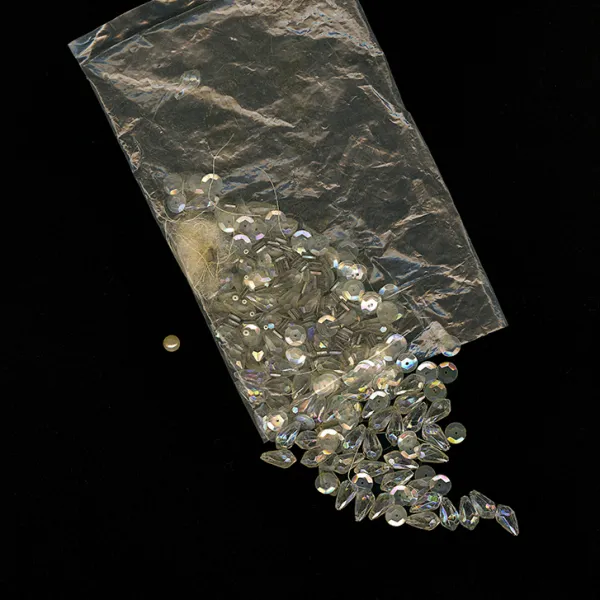

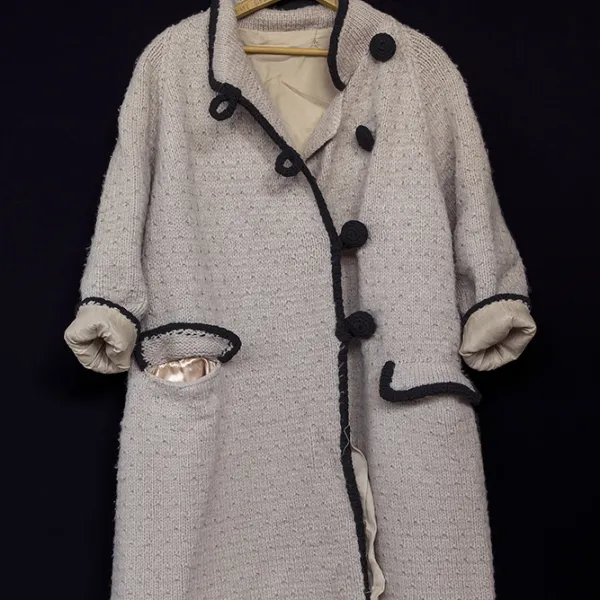

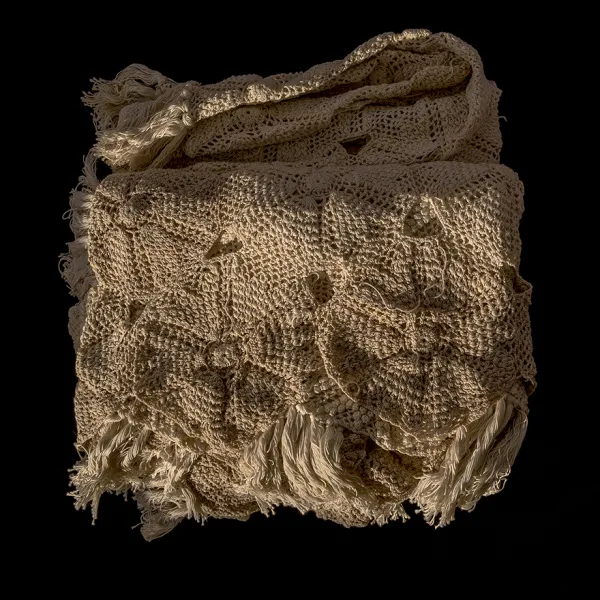

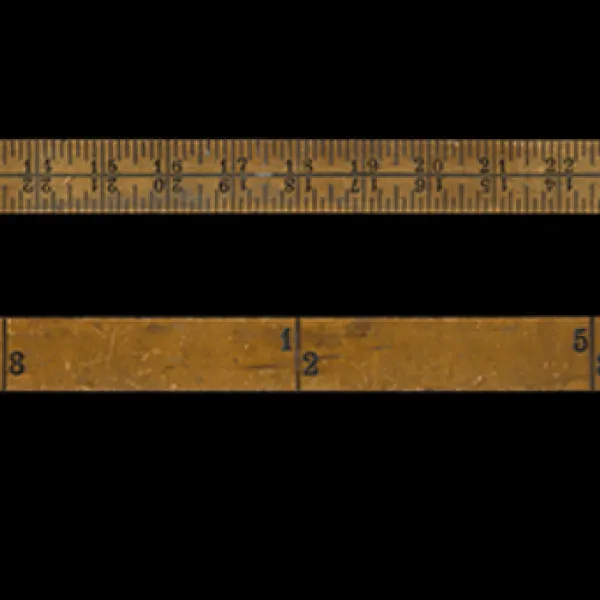

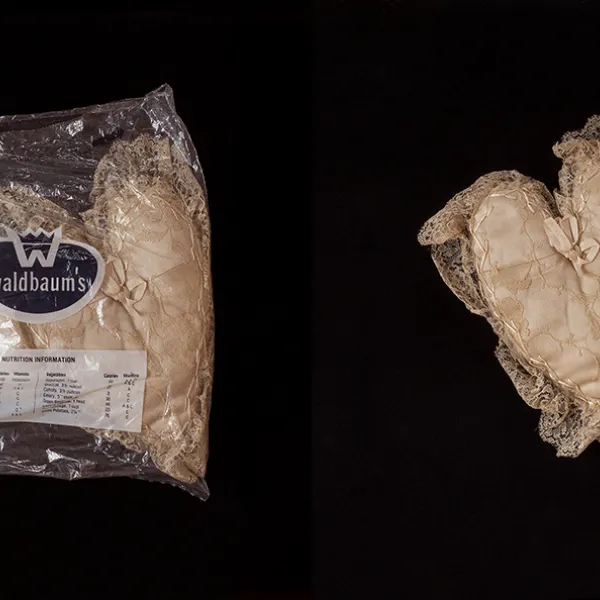

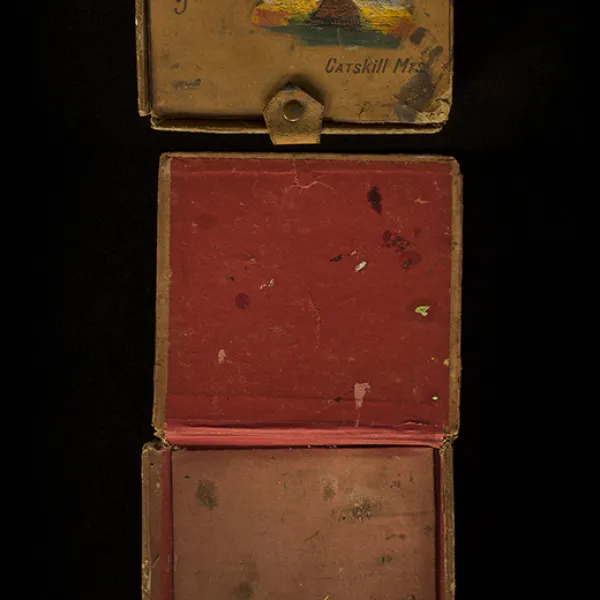

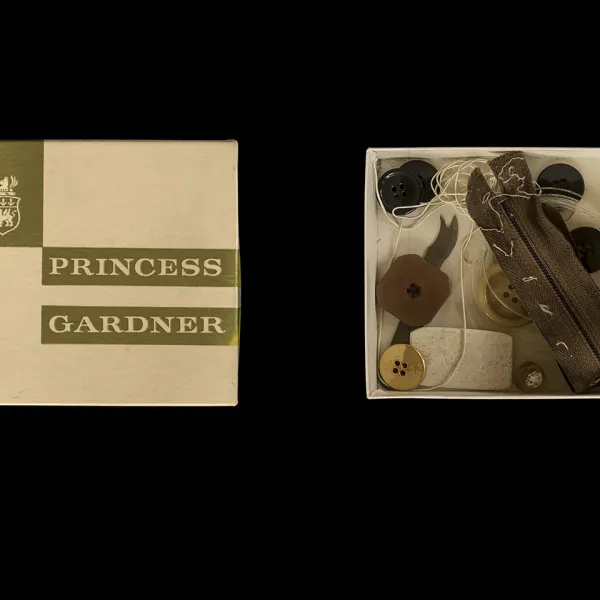

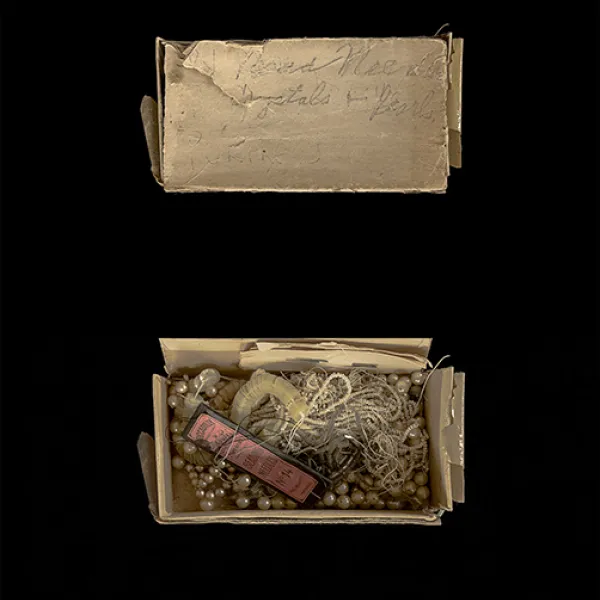

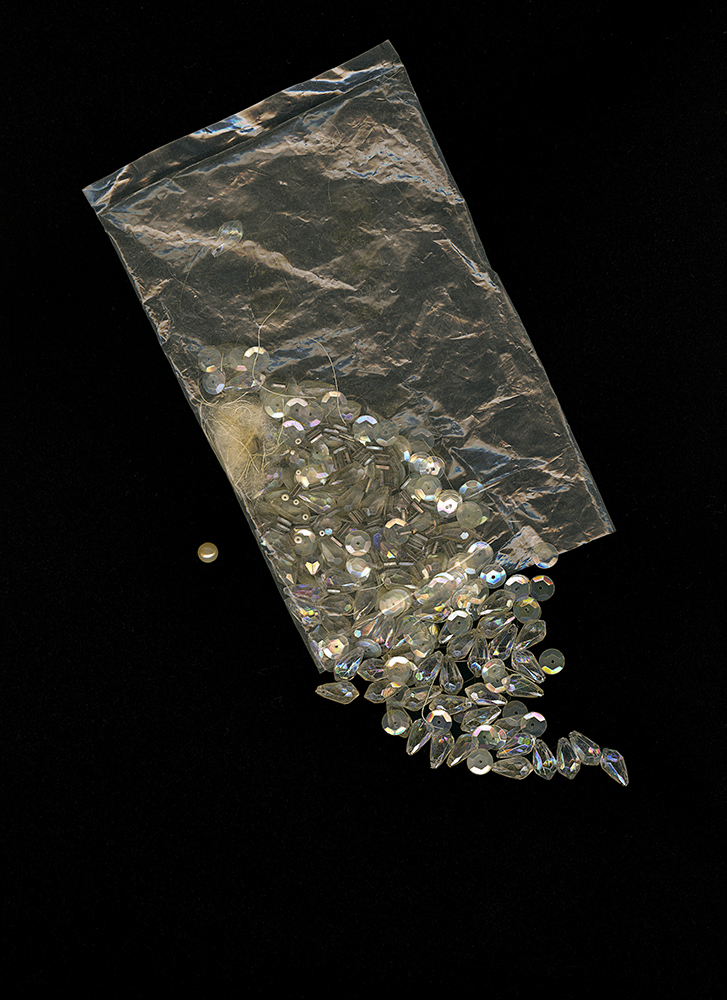

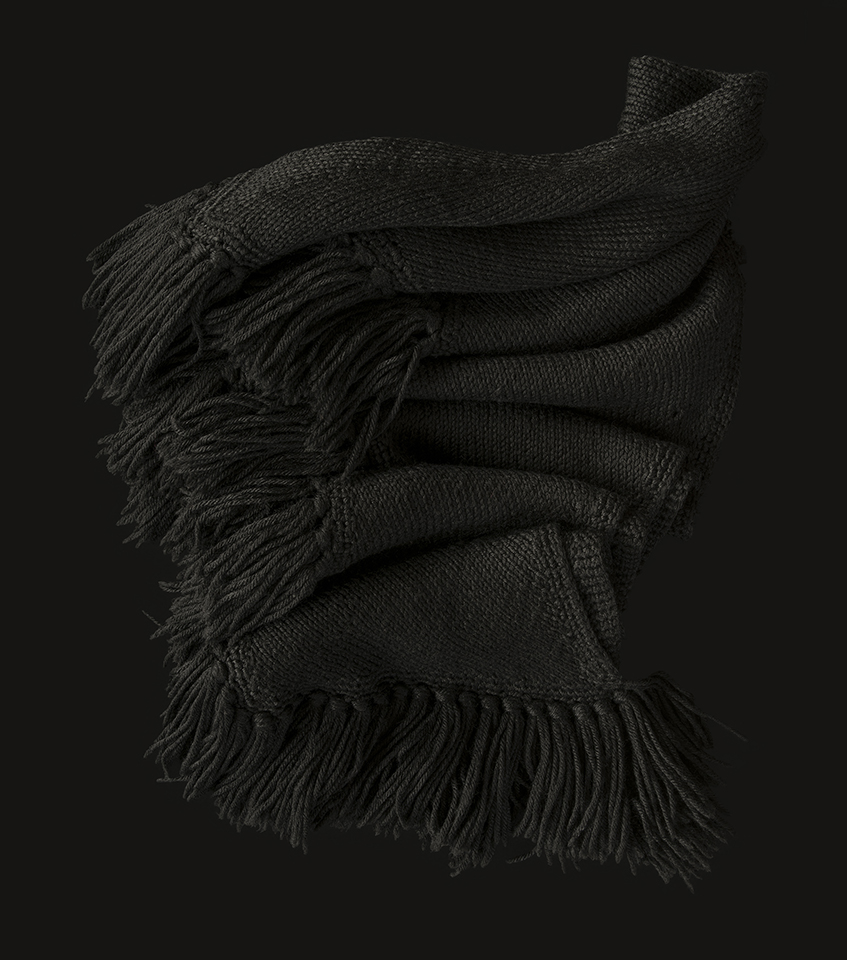

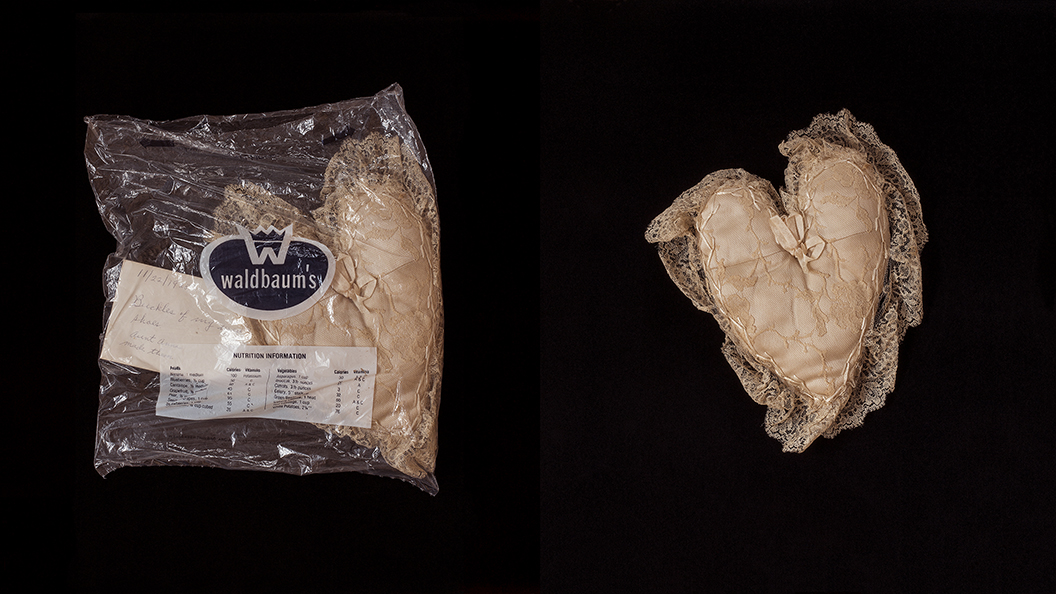

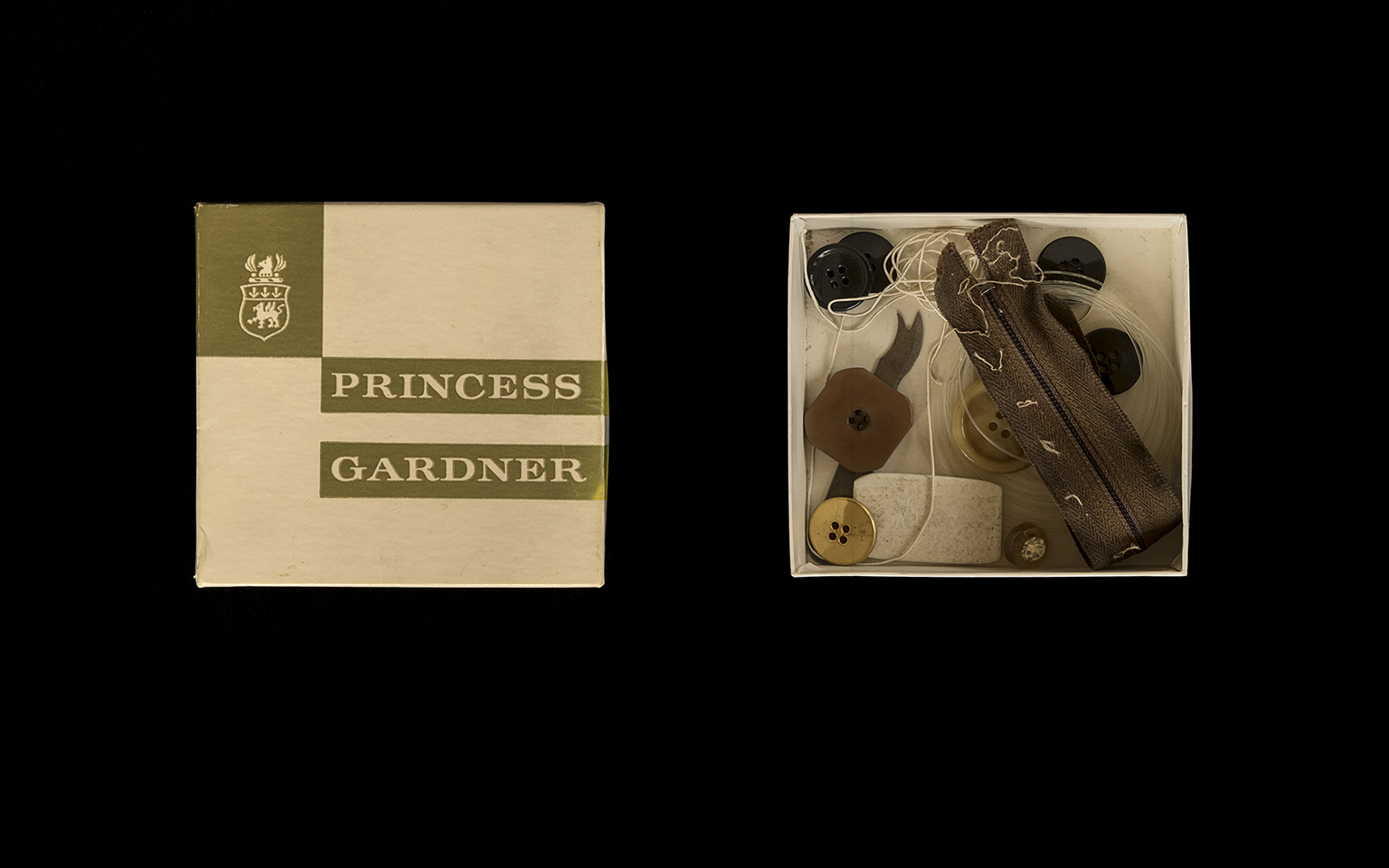

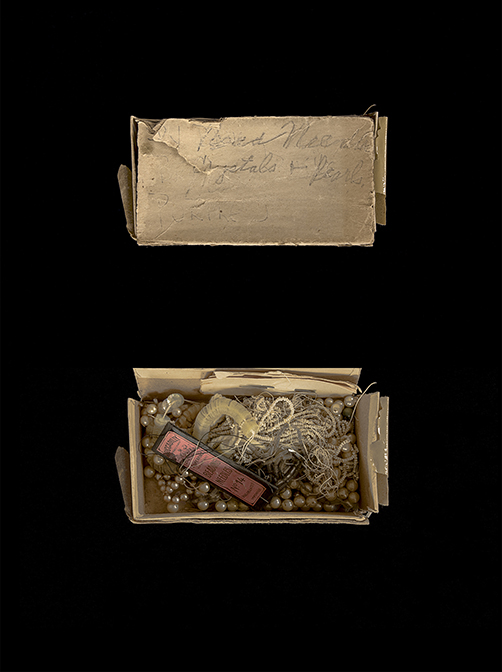

As an extension of the lifecycles project, lifecycles objects focuses more specifically on objects created and collected since the 1920s. My photographs of these objects suggest narratives and personal histories that are informed by my curiosity and connections to the individuals who made and owned these objects. I am interested in the materiality and presence of the objects, the creative process in making the objects, as well as the qualities that reference a lived experience.

These utilitarian objects, garments and materials were made and used by women in my family: Sarah; Anna; Renee; Gertie and Ellie. Despite the fact that these women worked outside the home, the domestic environment was a place in which they had more control. It provided an acceptable realm for women to explore creative ideas. They could make functional objects, sometimes out of necessity, while utilizing artistic concepts. This collection of items demonstrates these women were inventive and serious makers who cared deeply about the quality of their craft. In addition, they represent a collective history of making utilitarian items, shared by generations of Native, immigrant, and descendants of slave women.

I was surprised by how strongly I connected emotionally with these women and their creative process, in particular with my grandmother. For Anna, her productivity was not only out of necessity, she also had a creative need to make these things. At the age of twenty she made her own wedding dress, veil, bouquet, ring pillow and shoe buckles using remarkable flair, detail and imagination. Twenty-two years later, she reimagined and cut apart the fabric and lace for her daughter’s wedding dress. She taught herself how to paint with oils, replaced wire lampshade covers, and designed hats for Ranel, the millinery store she owned. Those hat designs exist only in photographs atop the heads of Renee, Anna and Ellie.

Anna sorted and stored her beads in coffee, cornstarch, tack and pill bottles. Her reused boxes held a torn-out zipper, tailors’ chalk, sequins, threads, needles and more beads. Saved threads were found wound around a matchbook and button card. The individual items display exquisite choices of colors, and textures, while the sensuous, silky fabric linings are attached with imperfect hand-stitching. A long piece of yarn with beads had been intentionally unraveled. It’s previous existence as a knitted form mysteriously unknown.

As a whole, the objects suggest personal histories and narratives that are simultaneously concrete and elusive.

Linda Brooks is a fiscal year 2015 and 2018 recipient of an Artist Initiative grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board. This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.

Image Gallery

Click an image to view in larger size